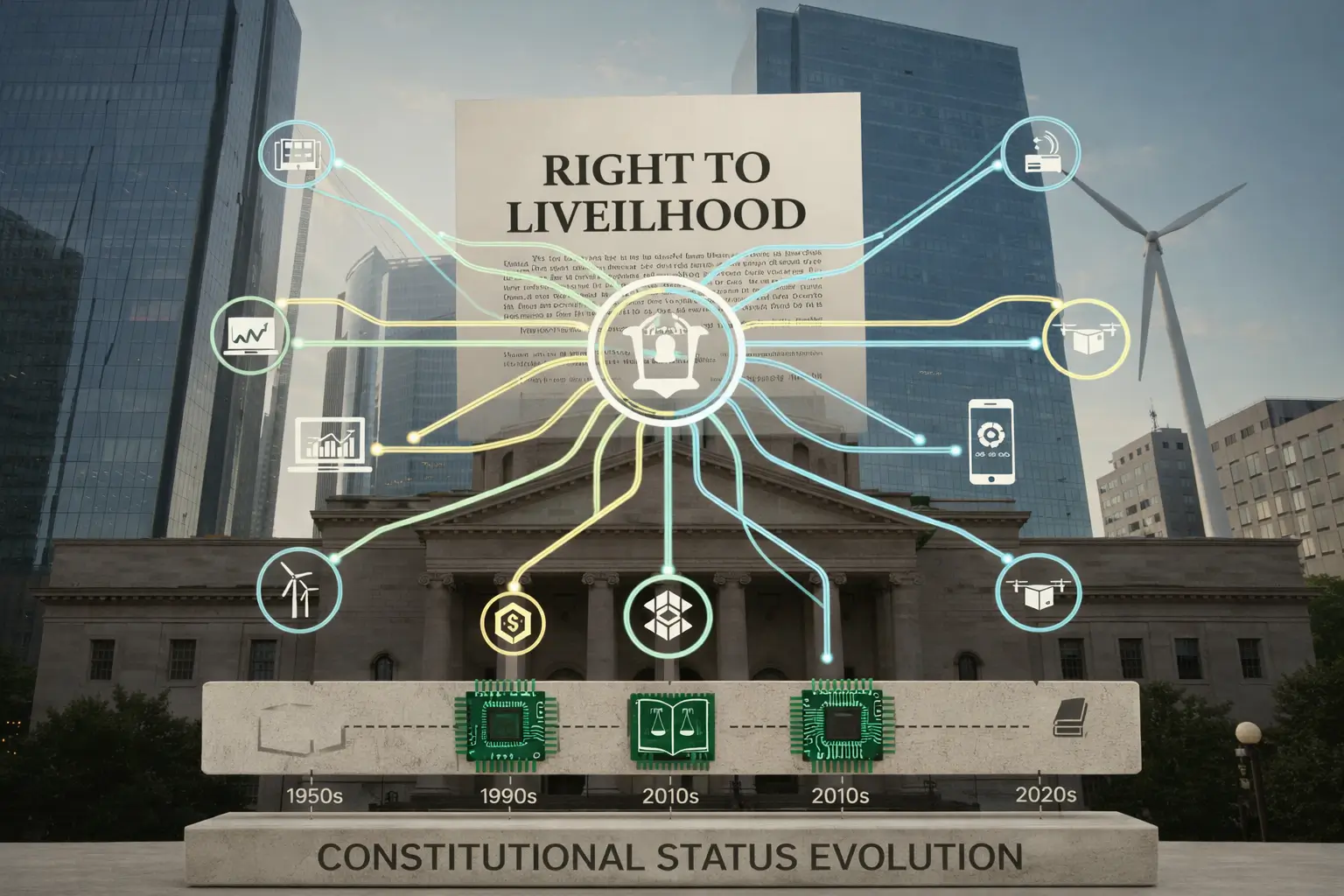

Right to Livelihood: Has the constitutional status evolved to accommodate the needs of current economy?

- Author (s) NEERAJ SHEKHAR

- Co-Author (s) UJJWAL ASHUTOSH

Table of Contents

INTRODUCTION

In any economy, people’s livelihoods, their means of earning and feeding themselves, depend on the prevailing sectors and jobs. In a primarily agrarian economy, land, water and common resources are critical to most people’s survival. As India’s economy shifted from agriculture to industry and services, livelihoods also shifted. Today India is a services- and technology-oriented economy, and many workers are in informal jobs. In fact, an estimated 90% of Indian workers are in informal employment.1 New platforms like ride-hailing or delivery apps have created a gig economy, with about 7.7 million gig workers in 2020-21, expected to grow to 23.5 million by 2029-30. In rural India, livelihood often meant land tenure or village work, while today it includes whether a truck driver or delivery rider can earn enough each day. These changes mean that as the sources of livelihood change, our understanding of “right to livelihood” too must develop. The Constitution’s Directive Principles even urge the State to ensure that citizens have “the right to an adequate means of livelihood”. This paper explores the legal foundations and evolution of the right to livelihood in India, and examines its meaning for modern workers especially gig and informal workers.

WHAT IS THE RIGHT TO LIVELIHOOD?

India’s Constitution does not explicitly define or mention the word “right to livelihood,” but the Supreme Court has read it into Article 21, right to life, and related provisions to define the essence of it.2 It has recognized that Article 21 guarantees more than mere survival. In Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India, the Court held that “life” in Article 21 must be understood as life with dignity and personal liberty.3 Building on that, the Court in Olga Tellis v. Bombay Municipal Corporation4 famously ruled that “the right to life includes the right to livelihood”. The case dealt with the pavement dwellers, who were to be evicted from their slums, and the Court agreed they would lose their jobs and means of living. The Court explained that no one can live without means of living; if a person’s livelihood is taken away, his life is essentially destroyed. The judgment noted that deprivation of livelihood to the point of starvation for a worker or family would “make life impossible to live,” and thus would violate Article 21 unless done with fair legal process.

The Court repeatedly emphasized the link between work and life. It pointed out that the Directive Principles themselves enshrine this goal. For example, Article 39(a)5 directs the State to secure “the right to an adequate means of livelihood” for citizens, and Article 41 directs it to make provision for the right to work in cases of unemployment.6 The Supreme Court observed that if the State is obliged to secure livelihood, it would be “sheer pedantry” to exclude livelihood from the right to life. Thus, any law that deprives a person of livelihood without just and fair procedure can be challenged as violating Article 21.

Other judgments have reinforced this idea. For example, Chandrabhan Tale v. State of Maharashtra7 involved a suspended police constable whose meager subsistence allowance of ₹1 per month was challenged. The Court struck down that rule. It emphasized that government jobs are a public resource, while writing that “public employment is the property of the nation … a national wealth which all citizens are equally entitled to share”. Even though the case was decided largely on Article 148 and Article 311 dealing with fair procedure in service,9 the Court in Chandrabhan Tale made it clear that employment is essential to life, reducing a worker’s allowance to starvation levels would effectively kill the right to life. The concurring judges warned that “it would be the death of the civil servant and the members of his family due to starvation” if the rule were allowed.

In Delhi Development Horticulture Employees’ Union v. Delhi Administration,10 the Court again discussed the principle. The bench recognized that India has not made livelihood a fundamental right due to practical constraints, but it emphasized that Article 41 in Directive Principles of State Policy still “enjoins upon the State to make effective provision for securing [livelihood] ‘within the limits of its economic capacity and development’”. In short, the Court viewed livelihood as a core part of life’s dignity.

Building upon such precedents the courts continued to deliver several judgements such as Francis Coralie Mullin v. Delhi11 establishing that the Constitution protects livelihood within the ambit of life and personal liberty. Therefore, Indian courts treat livelihood as an essential facet of life, while not enumerated as a separate fundamental right, its deprivation is subject to the same fair-procedure guarantees under Article 21.12

Image Source: india spend

ECONOMIC TRANSITIONS AND GIG WORKERS

As India’s economy changed from being mostly rural and based on agriculture to being more industrial and service-based, the kinds of jobs people do have changed a lot. In the first few decades after independence, most people made a living by farming or doing crafts in their villages. Land or common grazing could be very important for making a living. Factory and office jobs in cities became available quickly as a result of rapid industrialization. Services and digital businesses are the most important parts of India’s economy today. A lot of Indians now work in cities, which are often far from their ancestral villages. A lot of them work in factories, offices, stores, or more and more in informal service jobs.

A very large part of India’s workforce is still informal, which is important. WIEGO, an international group that collects labour statistics, says that “Employment in India is overwhelmingly informal.”13 About 80% of workers in Delhi and 90% of all workers in India are in informal arrangements. A lot of informal workers are migrant workers who move from poorer states to cities to find work. They often do not have formal job contracts or social security. The landscape of the gig economy has shifted considerably in recent years. Gig workers, those who earn their keep through digital platforms and short-term contracts, are at the heart of this transformation.14 This includes ride-hailing drivers like Ola and Uber, delivery riders for services like Zepto, Blinkit, Swiggy, Zomato, and many more. This kind of work is flexible, but it can also be risky. Companies usually call gig workers “self-employed” or “contractors,”which means they do not get the same protections and benefits as regular workers, like minimum wage, a provident fund, or ESI.15

Because of their job, these workers face many challenges that could threaten their right to livelihood. In gig work, most of the risks are on the worker instead of the employer, which is different from regular jobs. Workers have to pay for tools, cars, health care, and time off. Income is based on changing demand, platform algorithms, and customer ratings, which are mostly things that the worker cannot control. The Supreme Court has ruled that the right to life encompasses the need for livelihood security. The inherent uncertainty of this situation, however, undermines that security. If a person cannot reliably foresee whether they will earn enough to cover their essential expenses, it’s difficult to guarantee a life of dignity. The recent, large-scale demonstrations by delivery workers highlight the precariousness of their circumstances. Workers said that unclear rating systems, penalties, and sudden changes in incentives made their pay unstable, which put their ability to survive at risk.

A recent survey of platform delivery drivers found that full-time drivers work very long hours, on average over 50 hours per week and some up to 90 hours to make ends meet. The study found that drivers made about ₹170 per hour before expenses, but after paying for gas and maintenance, which is about 32% of their pay, they only took home about ₹115 per hour. A lot of people borrow money to buy bikes and smartphones for work, so not knowing how much money they will make can lead to debt. Also, more than half of the gig workers in one study were from other areas, which shows that platform jobs are often part of the move from rural to urban areas.

In this situation, gig workers and labour advocates say that not having social security and having low, unstable pay are violations of basic rights and their “right to livelihood.” A recent petition to the Supreme Court in the case of IFAT v. Union of India says that platform workers like app-based taxi and delivery drivers cannot get the protections that formal workers do because they are not considered “employees.”

The petitioners argue that denying social security benefits constitutes exploitation via forced labour. They contend that the lack of essential benefits and equitable compensation violates Articles 21 and 23 of the Constitution. These articles safeguard the right to work, earn a livelihood, and enjoy decent working conditions. As a result, people are now pressing the government and the courts to clarify if gig workers are covered by the Unorganised Workers’ Social Security Act of 2008. This would provide them with some basic protections, including insurance, pensions, and a provident fund.

We await the resolution of the case; however, it is evident that the definition of livelihood evolves with economic transformations. In a service-oriented and platform-centric economy, a stable income may rely on utilizing smartphone applications and maintaining flexible work hours. The antiquated laws and practices failed to anticipate this transformation. What measures can be implemented to ensure that app-based workers can provide for their families? Can platform firms be held responsible for the welfare of its employees? How does the Constitution’s guarantee of a dignified existence pertain to a worker earning ₹115 per hour?

MODERN ADVANCEMENTS & SAFEGUARDS

The new economy presents significant threats to the right to a livelihood, extending beyond just working conditions. The Constitution states that everyone has the right to a life of dignity, and the Supreme Court has repeatedly ruled that life cannot be sustained without the necessary resources. But a lot of gig and informal workers today live in situations where their income is unstable, fragile, and easy to disrupt. They often do not have basic protections like paid sick leave, guaranteed minimum work, or social security. Because of this, one illness, accident, or short-term loss of work can make it impossible for them to support themselves and their families. In these cases, the threat is not only financial trouble, but also a direct violation of the constitutional promise of a dignified life.16

The State has started to see policies not just as ways to regulate work but also as ways to protect people’s livelihoods. The most important step is the Code on Social Security, 2020, which is the first law to officially recognize gig workers and platform workers.17 From a constitutional perspective, this acknowledgment is significant because it recognizes these workers as a distinct group, thus mandating legal protection for their livelihood.

Under the Code, several mechanisms attempt to reduce livelihood vulnerability:

- Social Security Fund: Digital platform companies must contribute a small percentage of their turnover to a dedicated fund for gig workers.18 This fund is designed to back programs like life insurance, disability benefits, healthcare, maternity leave, and retirement pensions.19 These measures aim to prevent sudden shocks, illness, injury, old age, from destroying a person’s ability to survive, thereby protecting the continuity of livelihood rather than merely improving working conditions.

- Portable Benefits: Workers receive a unique Aadhaar-linked identification through the e-Shram portal. Because gig workers frequently shift between platforms, traditional employer-based benefits are ineffective. Portability means a worker’s social security benefits are retained, providing a safety net regardless of job changes.20

- Career centers and skill support services: Modern employment exchanges, are there to connect people with jobs and training. This matters because, from a livelihood standpoint, the right to earn a living encompasses not just protection from income loss but also access to ways to make money.21

- Registration and grievance mechanisms22: A national database of informal workers, and formal complaint channels are the state’s acknowledgment that livelihood insecurity frequently stems from a lack of visibility.23 Legal recognition makes it easier to design targeted welfare schemes and respond to systemic problems.

These changes are a big step in the right direction. Gig workers, previously excluded from the purview of formal labour protections, are now recognized as individuals whose fundamental requirements necessitate safeguarding. This emphasis on dignity and safety aligns with the stipulations of Article 21 of the Constitution. Furthermore, the legal classification of a worker group facilitates judicial assessment of the efficacy of state policies in safeguarding their employment.

However, mere recognition does not suffice to fully secure the right to a livelihood. Experts contend that additional measures are essential to ensure that workers can earn a sufficient income to maintain a dignified standard of living. Minimum income guarantees, fair pricing systems, and more transparent algorithmic decision-making are some suggested changes. Without these protections, workers could still have jobs on paper, but they might not be able to support themselves financially.

In addition, broader social protection programs are also important. The rural employment guarantee program in India shows that the government can directly make sure that people have a minimum level of income by giving them jobs. Giving similar guarantees to cities or setting up income support systems could help people whose jobs depend on markets that change quickly. These kinds of policies see livelihood as a responsibility of society as a whole, not just of the person who has it.

The main question is not if people have jobs, but if they have safe ways to live. A person may work long hours but still not be able to meet their basic needs. From a constitutional standpoint, this scenario is troubling because the right to life necessitates more than mere existence; it demands conditions that render life significant and dignified.

Image Source: hindustan times

RIGHT TO LIVELIHOOD: GIG WORKERS AROUND THE GLOBE

The idea of a “right to livelihood” is not unique to India. Numerous nations acknowledge, albeit through diverse approaches, the imperative that individuals possess the means to secure a livelihood commensurate with their dignity. Nevertheless, the legal standing, implementation strategies, and tangible safeguards associated with this right exhibit considerable variance. Certain nations enshrine the right to work or livelihood explicitly within their constitutional frameworks, whereas others safeguard it through welfare provisions, labour regulations, or human rights obligations, rather than as a legally enforceable entitlement.

INTERNATIONAL LAW FRAMEWORK:

On the international stage, the right to livelihood primarily derives from the right to work, as articulated in international human rights instruments. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights 1948 [“UDHR”] states in Article 23 that everyone has the right to work, to free choice of employment, and to just and favourable conditions of work.24 Similarly, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights [ICESCR], 1966,25 to which India and most countries are parties, recognizes the right to gain one’s living by work freely chosen or accepted26, as well as the right to just and favourable working conditions27 and social security28. Unlike civil and political rights, these socio-economic rights are often subject to “progressive realization.” States must take steps within their available resources to achieve them gradually.

This approach acknowledges that guaranteeing livelihood depends heavily on economic capacity, employment opportunities, and social policy.

UNITED STATES:

The United States does not recognize a constitutional right to livelihood or work. The U.S. Constitution mainly protects negative liberties such as freedom from government interference rather than positive entitlements of government obligations to provide work or income.

Historically, during the early twentieth century, the U.S. Supreme Court sometimes protected economic freedom under the doctrine of “liberty of contract.”29 However, this did not translate into a right to employment.30 After the New Deal era, the Court shifted to allowing extensive government regulation of labour markets.

Today, protection of livelihood in the U.S. primarily comes from:

- Labour laws i.e. minimum wage, workplace safety, anti-discrimination

- Social welfare programs i.e. unemployment insurance, Social Security, food assistance

- Collective bargaining through unions which is though declining

Gig workers in the U.S. face similar issues as in India. Most platform workers are classified as independent contractors rather than employees. This classification excludes them from benefits such as minimum wage guarantees, overtime pay, unemployment insurance, and employer-provided healthcare. Some states have attempted reforms. For example, California enacted Assembly Bill 531 to reclassify many gig workers as employees, but companies successfully pushed for Proposition 22, which created a special category of workers with limited benefits but not full employee status.32 This illustrates the ongoing struggle to balance flexibility with livelihood security.

UNITED KINGDOM

The United Kingdom uses a middle-ground approach. It recognizes three types of workers: Employees, Workers (an intermediate category), and Self-employed individuals. Gig workers often fall into the “worker” category. This gives them some rights, like the minimum wage, paid leave, and protection from discrimination, but not all the benefits of full employment.

A major change happened in 2021, when the UK Supreme Court ruled that Uber drivers are “workers,” not independent contractors.33 Consequently, these individuals gained access to minimum wage compensation and paid vacation time. This ruling substantially enhanced the financial stability of platform drivers and subsequently shaped analogous discussions globally.

Although the United Kingdom lacks a constitutional provision explicitly safeguarding the right to a livelihood, it upholds a robust welfare state. Universal healthcare, unemployment benefits, housing assistance, and pension schemes collectively serve to shield citizens from poverty, even in the event of job loss.

EUROPEAN UNION

Many European countries provide the strongest practical protection of livelihood, even without explicitly using that term. The European social model combines labour rights with extensive social security systems. The European Social Charter recognizes the right to work, fair remuneration, safe working conditions, and protection against poverty and social exclusion. EU member states typically guarantee statutory minimum wages, Strong labour unions and collective bargaining, Unemployment insurance, Universal healthcare and Family benefits and pensions.

CONCLUSION

Right to livelihood has emerged as a fundamental thread running through India’s constitutional fabric. The Supreme Court has made it clear that life without the means to live is no life at all. Over decades, the judiciary has broadened Article 21’s scope to protect workers’ subsistence, and the legislature is now extending protections to the new class of platform and informal workers. Today, as India’s economy evolves, the right to livelihood remains as important as ever: whether a person labours in a field, a factory or on an app, the law aims to preserve the dignity of living by safeguarding their ability to earn. Ensuring that promise in practice through fair laws, robust social security, and inclusive economic policies, is the continuing challenge of our time

FOOTNOTES

+919458479236