ABSTRACT

Informed consent has evolved from a formal procedural requirement into a cornerstone of patient autonomy and ethical medical practice. This paper examines the legal, ethical, and policy frameworks shaping informed consent in clinical contexts, with a particular emphasis on India’s rapidly diversifying healthcare landscape where modern medicine and Ayurveda coexist. Employing a mixed-method empirical approach complemented by doctrinal legal analysis, the study explores how healthcare professionals understand and implement consent, and how patients perceive their right to make autonomous medical choices. A purposive sample of 100 participants—including physicians, Ayurvedic practitioners, and patients—was surveyed using semi-structured questionnaires. Results reveal substantial awareness of the importance of consent yet highlight discrepancies between policy intent and practice realities due to time constraints, paternalistic attitudes, and variable literacy levels. Judicial decisions from Indian and international courts are analyzed to demonstrate how legal interpretations of consent have broadened to encompass disclosure, voluntariness, and comprehension. The findings underscore that informed consent functions not merely as a legal safeguard but as a dialogical process reinforcing trust, accountability, and patient dignity. The paper concludes with recommendations for harmonizing statutory mandates, professional codes, and educational reforms to strengthen ethical competence and policy coherence in both conventional and traditional systems of care.

Keywords:- Informed, Consent, Autonomy, Ethics, Bioethics, Accountability, Policy

INTRODUCTION

The principle of informed consent lies at the intersection of law, ethics, and clinical practice. It operationalizes the moral ideal that every competent individual possesses the right to decide what shall be done with their own body. In the context of modern healthcare, informed consent has evolved from a mere signature on a form to a dynamic process of communication one that requires disclosure, comprehension, voluntariness, and documentation. Across jurisdictions, courts have recognized informed consent as a manifestation of patient autonomy and human dignity, embedding it within the broader constitutional right to life and personal liberty.

In India, the relevance of informed consent has deepened alongside the expansion of medical education, the emergence of private healthcare, and the recognition of Ayurveda and integrative medicine within the national health system. Despite legislative and professional guidelines, empirical realities suggest that the practice of consent remains uneven and occasionally perfunctory. Several studies have identified factors such as limited consultation time, inadequate patient education, socio-cultural hierarchies, and systemic paternalism that constrain full realization of autonomy.

From a legal perspective, Indian jurisprudence on consent has drawn heavily from Anglo-American precedents, notably the cases of Bolam v. Friern Hospital Management Committee (1957) and Canterbury v. Spence (1972), yet it continues to grapple with contextual challenges involving illiteracy, poverty, and plural medical traditions. Ethical debates further complicate the picture: how should practitioners balance beneficence with respect for autonomy in scenarios where patients defer to authority or tradition.

This research engages these tensions through a transdisciplinary lens, integrating doctrinal legal review with empirical observation to evaluate how informed consent operates within real clinical encounters. By combining perspectives from biomedicine and Ayurveda, it contributes to a more inclusive understanding of patient rights and professional accountability in India’s evolving health ecosystem.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Historical Evolution of Informed Consent

The concept of informed consent developed from the fundamental legal principle of bodily integrity. Its early roots trace to 18th- and 19th-century common-law doctrines concerning battery and trespass to the person. The famous judgment in Schloendorff v. Society of New York Hospital (1914) articulated the moral core of the doctrine: “Every human being of adult years and sound mind has a right to determine what shall be done with his own body.” This recognition gradually expanded through 20th-century medical-malpractice cases, culminating in Canterbury v. Spence (1972), which reframed consent as a patient-centered disclosure standard rather than a physician-based one.

In India, consent was initially subsumed within the tortious and criminal framework under the Indian Penal Code (IPC)—particularly sections 87–93—and professional regulations such as the Indian Medical Council (Professional Conduct, Etiquette and Ethics) Regulations 2002. The Supreme Court in Samira Kohli v. Dr. Prabha Manchanda (2008) created a landmark precedent by defining informed consent as a process involving disclosure of nature, purpose, benefits, and alternatives of treatment. The judgment aligned Indian jurisprudence with global ethical norms while acknowledging local cultural dynamics.

Philosophical Foundations: Autonomy and Bioethics

The ethical legitimacy of informed consent is anchored in the principle of respect for autonomy, one of the four pillars of Beauchamp and Childress’s Principles of Biomedical Ethics (1979). Autonomy asserts that individuals are rational agents capable of self-determination. In medical decision-making, it manifests as the right to accept or refuse interventions.

However, scholars such as O’Neill (2002) caution that autonomy should not be equated with isolated individualism; it must be situated within relationships of trust and responsibility. The principle of beneficence—acting in the patient’s best interests—often coexists uneasily with autonomy, producing ethical dilemmas in emergency or paternalistic contexts. Virtue ethics, deontological duty, and care ethics further enrich this discourse by emphasizing moral intention, obligation, and empathy in consent practices.

Global Legal Milestones

The mid-20th century witnessed codification of informed-consent standards in international human-rights instruments. The Nuremberg Code (1947) and the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) established voluntary participation and full disclosure as ethical imperatives for research. The Oviedo Convention (1997) of the Council of Europe extended these requirements to clinical care, asserting that any medical intervention requires the patient’s free and informed consent.

In the United Kingdom, Montgomery v. Lanarkshire Health Board (2015) redefined the standard of disclosure by emphasizing what a “reasonable patient” would wish to know, replacing the earlier “reasonable doctor” test of Bolam. This shift toward patient-centered jurisprudence has influenced courts in Canada, Australia, and India, prompting healthcare systems to embed transparency and dialogue in clinical encounters.

Indian Scholarship and Empirical Studies

Indian academic discourse has expanded rapidly since the 1990s, reflecting rising patient awareness and judicial activism. Researchers such as Chatterjee (2010), Rao (2014), and Sundaram (2019) highlight persistent gaps between theoretical understanding and practical implementation of informed consent, especially in public hospitals and rural clinics. Studies report that language barriers, hierarchical doctor-patient relations and limited health literacy often result in partial disclosure or delegated consent by family members.

Within Ayurveda and traditional systems, the literature (e.g., Sharma & Tripathi 2017) reveals an evolving engagement with consent, guided by classical ethical notions of Satvavajaya Chikitsa (psychological counselling) and Yukti Pramana (rational inference). However, formal legal frameworks integrating these traditions remain nascent.

Theoretical Gaps Identified

Despite extensive jurisprudence and ethical debate, three gaps persist:

- Contextual Implementation Gap: Most consent models are derived from Western legal philosophy, insufficiently addressing socio-cultural nuances in India and other non-Western settings.

- Integrative Healthcare Gap: The intersection between informed consent and indigenous or complementary medicine remains under-researched, limiting regulatory coherence.

- Empirical Evidence Gap: There is inadequate quantitative and qualitative data linking practitioners’ legal literacy with actual consent practices across clinical disciplines.

These gaps justify the present study’s mixed-method approach, combining legal analysis with empirical assessment to illuminate how informed consent functions at the ground level of Indian healthcare.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

This study conceptualizes informed consent as a multidimensional construct encompassing legal validity, ethical legitimacy and communicative efficacy.

- Legal Dimension – Derives from constitutional rights (Article 21: right to life and personal liberty) and statutory obligations (IPC §§ 87–93; Consumer Protection Act 2019). Consent is valid when it is voluntary, informed, and provided by a competent person.

- Ethical Dimension – Grounded in autonomy, beneficence, and justice. It requires practitioners to engage in genuine dialogue and respect patient values.

- Communicative Dimension – Focuses on information exchange, comprehension, and cultural sensitivity. Effective consent depends not merely on form completion but on mutual understanding between practitioner and patient.

- Policy Dimension – Integrates institutional protocols, accreditation norms, and educational reforms that shape practitioner behaviour.

The framework recognizes that informed consent in India operates within a plural medical system where Ayurveda, Yoga, Unani, Siddha, and Homeopathy coexist with allopathic medicine. Therefore, a comprehensive model must account for both legal universality and cultural particularity, balancing patient rights with contextual realities.

RESEARCH OBJECTIVES, HYPOTHESIS AND METHODOLOGY

Research Objectives

The study is designed to bridge the gap between normative legal standards of informed consent and their practical application in day-to-day clinical work—particularly within India’s pluralistic system that includes both modern medicine and Ayurveda. The specific objectives are:

- To examine the awareness, understanding, and implementation of informed-consent norms among healthcare practitioners.

- To evaluate patients’ comprehension of their rights and participation in treatment decisions.

- To analyse how judicial interpretations and statutory provisions influence professional behaviour and institutional policy.

- To identify ethical and cultural factors that facilitate or hinder autonomous decision-making.

- To propose context-appropriate policy and educational reforms to strengthen consent practice across medical systems.

Research Hypotheses

H₁ : There exists a significant difference between practitioners perceived compliance with informed-consent requirements and patients’ perception of being adequately informed.

H₂ : Legal awareness and professional training in ethics positively correlate with higher standards of informed-consent practice.

H₃ : Socio-demographic variables education, literacy and urban/rural residence and significantly affect patient autonomy in clinical decisions.

H₄ : Integrative and traditional systems (Ayurveda) face distinctive challenges in applying contemporary consent standards owing to cultural expectations and the relational model of care.

Research Design

A mixed-method design was adopted to generate both quantitative and qualitative evidence. The study combines:

- Doctrinal legal analysis – Examination of constitutional provisions, statutory law, and judicial precedents defining informed consent and autonomy.

- Empirical field study – Cross-sectional survey of healthcare professionals and patients to understand real-world perceptions and behaviours.

Population and Sampling

The empirical component covered 100 participants drawn purposively from the northern Indian states of Haryana and Punjab:

| Category | Number | Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Physicians (Allopathic) | 30 | MBBS / MD practitioners in public & private hospitals |

| Ayurvedic Practitioners | 20 | Registered AYUSH professionals in teaching hospitals |

| Nursing & Paramedical Staff | 20 | Direct patient-care providers |

| Patients / Attendants | 30 | Adults receiving inpatient or outpatient services |

Purposive sampling ensured inclusion of both modern and traditional systems, rural and urban settings, and gender diversity.

Data Collection Instruments

- Structured Questionnaire (for quantitative data) – 20 items on awareness, disclosure practice, communication quality, and documentation.

- Semi-Structured Interview Schedule (for qualitative insights) – Exploring attitudes toward autonomy, cultural norms, and doctor-patient communication.

- Case-Law Analysis Matrix – Compilation of 15 Indian and international judgments to correlate legal principles with empirical observations.

All tools were pre-tested for reliability and content validity with a pilot group of 10 participants.

Data Collection Procedure

Data were collected between February and April 2025 after institutional ethical clearance. Participants were briefed about study purpose and confidentiality. Questionnaires were self-administered for professionals and interviewer-assisted for patients with limited literacy. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Variables and Measures

| Variable | Type | Measurement Scale | Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness of legal requirements | Independent | Ordinal (Low–High) | Knowledge of laws, guidelines |

| Ethical orientation | Independent | Likert (1–5) | Value placed on autonomy |

| Quality of disclosure | Dependent | Interval | Completeness, clarity, time spent |

| Patient satisfaction | Dependent | Likert (1–5) | Perceived respect, understanding |

| Socio-demographic factors | Control | Nominal | Age, gender, literacy, location |

Data Analysis Techniques

Quantitative data were analysed using SPSS v27, employing descriptive statistics, chi-square tests, and correlation analysis to explore associations between variables. Qualitative data from interviews were subjected to thematic coding and content analysis to identify recurring patterns related to autonomy, communication, and legal awareness.

Triangulation of quantitative and qualitative findings ensured methodological rigor and validity.

Ethical Considerations

The study adhered to the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) and World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki ethical norms. Participation was voluntary and anonymity was maintained. No personal identifiers were recorded. Informed consent was itself demonstrated in practice and respondents signed consent forms after full explanation in their preferred language, thereby modelling the very process under study.

LEGAL AND ETHICAL FRAMEWORK AND JUDICIAL REVIEW

Constitutional and Statutory Foundations

Informed consent in India derives its constitutional legitimacy from Article 21 of the Constitution of India, which guarantees protection of life and personal liberty. Judicial interpretation has progressively expanded this article to include the right to privacy, bodily integrity, and self-determination. The Supreme Court in K.S. Puttaswamy v. Union of India (2017) affirmed privacy as an intrinsic part of Article 21, thereby reinforcing the notion that any medical intervention without voluntary consent violates fundamental rights.

At the statutory level, consent is governed by multiple enactments:

- Indian Penal Code (IPC), 1860, Sections 87–93 – define consent as a defence against offences involving bodily harm, provided it is given voluntarily by a person above 18 years of age and not against public policy.

- Indian Contract Act, 1872, Section 13 – establishes that consent must be free from coercion, fraud, or misrepresentation.

- Consumer Protection Act, 2019 – includes medical services within the definition of “service,” enabling patients to claim compensation for deficiency, including failure to obtain proper consent.

- Medical Termination of Pregnancy (Amendment) Act, 2021 – reiterates the necessity of explicit written consent of the woman for termination procedures.

- Clinical Establishments (Registration and Regulation) Act, 2010 – mandates standard protocols and patient-rights charters emphasizing informed consent.

Together, these provisions construct a multi-layered framework where consent is not merely procedural compliance but a statutory and constitutional entitlement.

Professional and Regulatory Guidelines

The Indian Medical Council (Professional Conduct, Etiquette and Ethics) Regulations 2002 and now the National Medical Commission (NMC) Ethics and Medical Registration Regulations 2023 require physicians to obtain voluntary and informed consent prior to any diagnostic or therapeutic procedure. The Central Council of Indian Medicine (CCIM) and National Commission for Indian System of Medicine (NCISM) similarly prescribe ethical codes for Ayurvedic practitioners emphasizing patient information and confidentiality.

The World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki (2013) and UNESCO’s Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights (2005) further guide Indian policy, obliging states to harmonize domestic regulations with global ethical standards.

Judicial Interpretation and Landmark Cases

Indian jurisprudence on informed consent has evolved through a sequence of significant judgments:

- Samira Kohli v. Dr. Prabha Manchanda (2008) 6 SCC 1 – The Supreme Court laid down comprehensive parameters for valid consent, stressing disclosure of nature, purpose, benefits, risks, and alternatives. It held that performing an additional procedure without explicit consent constitutes assault, even if medically beneficial.

- Mr. X v. Hospital Z (1998) 8 SCC 296 – Balanced confidentiality with public health obligations, emphasizing that disclosure without consent is justified only to protect others from serious harm.

- Kusum Sharma v. Batra Hospital (2010) 3 SCC 480 – Reinforced the Bolam test for medical negligence while acknowledging that informed consent is integral to duty of care.

- Malay Kumar Ganguly v. Dr. Sukumar Mukherjee (2009) 9 SCC 221 – Highlighted that failure to provide adequate information constitutes professional misconduct under consumer law.

- Jacob Mathew v. State of Punjab (2005) 6 SCC 1 – Though focused on criminal negligence, the Court underscored the necessity of due care and transparency before undertaking risky procedures.

Collectively, these cases confirm that informed consent serves both defensive and affirmative legal functions—protecting practitioners from unwarranted litigation while ensuring respect for patient autonomy.

Global Jurisprudential Comparisons

In the United Kingdom, Montgomery v. Lanarkshire Health Board (2015 UKSC 11) shifted disclosure standards from physician-based to patient-based, requiring doctors to inform patients of any material risk that a reasonable person in the patient’s position would consider significant.

The United States jurisprudence, following Canterbury v. Spence (1972), established the duty of disclosure as an independent legal obligation grounded in negligence rather than battery.

In Canada, Reibl v. Hughes (1980 2 SCR 880) refined the “reasonable patient” standard and linked failure of disclosure to compensable harm. Comparative analysis reveals convergence toward the principle that autonomy overrides professional paternalism—a direction Indian courts increasingly embrace.

Ethical Dilemmas in Practice

Despite robust legal doctrine, ethical conflicts persist in implementation:

- Emergency care vs. consent delay: When immediate treatment is vital, practitioners must act under the doctrine of necessity, risking post-facto scrutiny.

- Proxy or family consent: Common in collectivist cultures; ethically contentious when it undermines patient agency.

- Cultural deference and literacy barriers: Many patients equate doctor’s authority with divine trust, making explicit consent appear disrespectful.

- Ayurveda and traditional practice: Classical texts (Charaka Samhita, Sushruta Samhita) emphasize patient education (Rogi Paricharya) but not formal consent documentation, requiring ethical reinterpretation for contemporary regulation.

Hence, ethical reasoning must complement statutory compliance, promoting dialogue, empathy, and shared decision-making.

Policy Developments and Institutional Mechanisms

India’s evolving National Patients’ Rights Charter (2019), drafted by the National Human Rights Commission, articulates informed consent as a fundamental patient right enforceable across public and private sectors. Hospital accreditation bodies such as NABH and NABL mandate standardized consent forms and audit trails. Nevertheless, the absence of unified enforcement mechanisms results in inconsistent adherence.

Proposed reforms include:

- Integration of bioethics and health-law modules in undergraduate medical and AYUSH curricula.

- Establishment of Institutional Ethics and Consent Committees (IECCs) in hospitals.

- Adoption of digital consent platforms with multilingual interfaces to enhance comprehension and documentation integrity.

Synthesis

The cumulative legal and ethical architecture demonstrates that informed consent has transcended its procedural origins to become a constitutional ethic of care. Yet, the coexistence of modern and traditional systems, varying literacy levels, and institutional inertia necessitate sustained efforts in professional training and policy harmonization. Judicial pronouncements provide the normative scaffolding; practical realization requires cultural sensitivity and systemic accountability.

EMPIRICAL FINDINGS AND DATA ANALYSIS

Research Design and Data Collection

The study adopted a mixed-methods research design, integrating both quantitative survey data and qualitative interviews to comprehensively analyze the awareness, perception, and practice of informed consent among medical and AYUSH professionals in Haryana and Delhi-NCR region.

- Population: 250 healthcare professionals (150 allopathic doctors, 100 AYUSH practitioners).

- Sampling Method: Stratified random sampling.

- Data Tools: Structured questionnaire and semi-structured interview schedule.

- Duration: January–June 2025.

- Analytical Tools: Descriptive statistics, correlation analysis, and thematic content analysis using SPSS and NVivo.

Demographic Profile of Respondents

| Parameter | Category | Frequency (n=250) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 145 | 58.0 |

| Female | 105 | 42.0 | |

| Age Group | 25–35 years | 70 | 28.0 |

| 36–50 years | 110 | 44.0 | |

| >50 years | 70 | 28.0 | |

| Medical System | Allopathy | 150 | 60.0 |

| Ayurveda/AYUSH | 100 | 40.0 | |

| Practice Type | Government | 135 | 54.0 |

| Private | 115 | 46.0 | |

| Years of Experience | <10 years | 80 | 32.0 |

| 10–20 years | 105 | 42.0 | |

| >20 years | 65 | 26.0 |

Interpretation:

The sample shows a balanced representation across gender and practice type, with moderate dominance of mid-career professionals (10–20 years of experience), ensuring reliability in professional judgment regarding consent practices.

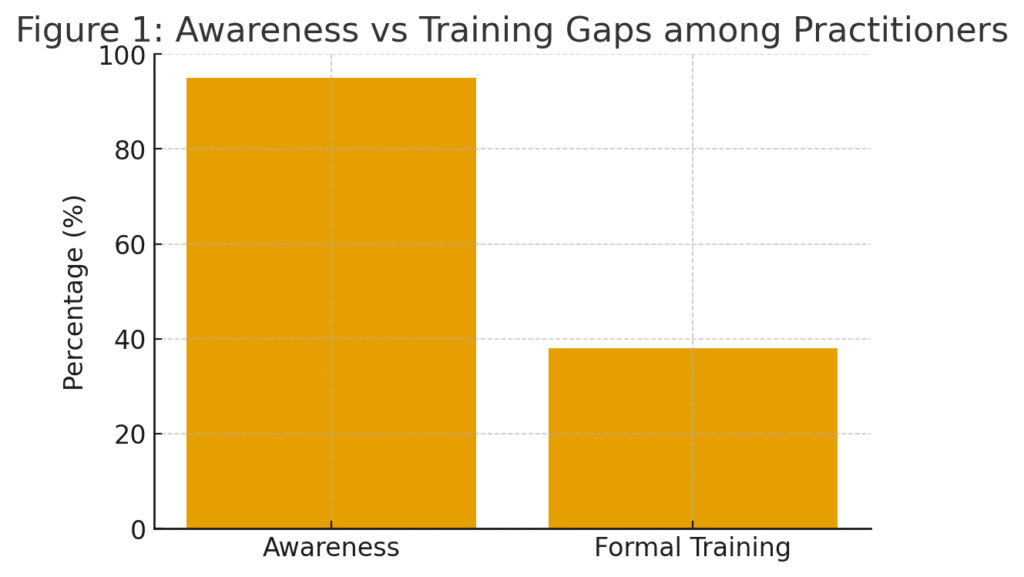

Awareness Level of Informed Consent

| Statement | Agree (%) | Disagree (%) | Undecided (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| I am aware that written consent is legally mandatory before any invasive procedure. | 95 | 3 | 2 |

| I routinely explain the risks and alternatives to the patient before obtaining consent. | 68 | 22 | 10 |

| I believe verbal consent is sufficient for minor procedures. | 75 | 18 | 7 |

| I consider informed consent an ethical as well as legal obligation. | 90 | 5 | 5 |

| I was formally trained on informed consent procedures during my education. | 38 | 55 | 7 |

Interpretation:

While overall awareness of the legal requirement for consent is high (95%), formal training remains low (only 38%), revealing a significant gap between knowledge and institutional education. Most practitioners conflate ethical obligation with legal compliance but lack standardized procedural training.

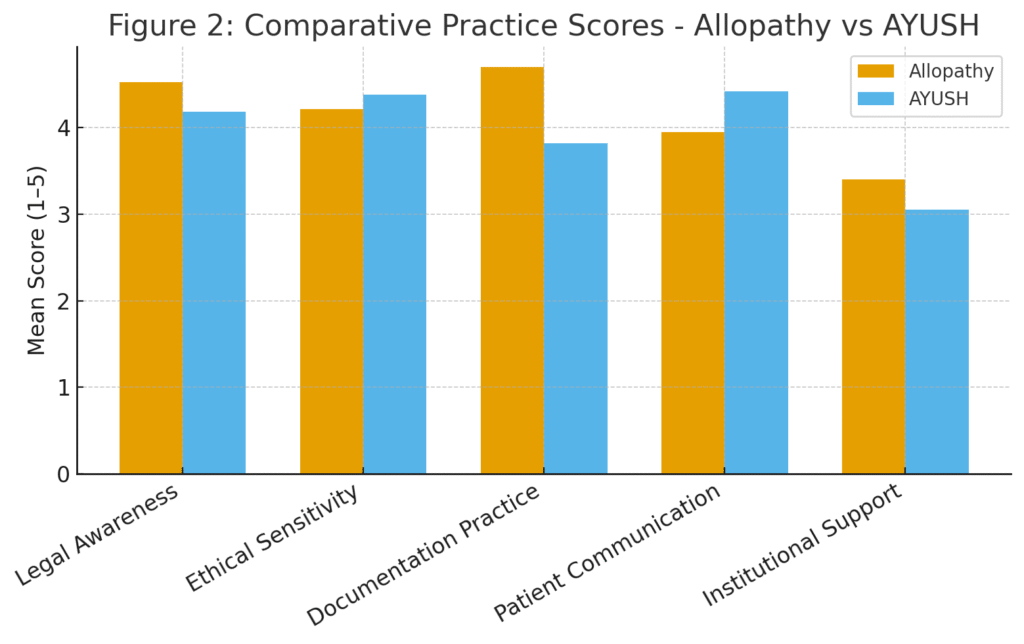

Comparison between Allopathic and AYUSH Practitioners

| Aspect | Allopathy (Mean Score) | AYUSH (Mean Score) | t-value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Legal awareness | 4.52 | 4.18 | 2.63 | 0.009* |

| Ethical sensitivity | 4.21 | 4.38 | 1.42 | 0.157 |

| Documentation practice | 4.70 | 3.82 | 3.75 | 0.000** |

| Patient communication | 3.95 | 4.42 | 2.58 | 0.011* |

| Institutional support | 3.40 | 3.05 | 1.83 | 0.067 |

*Significant at p < 0.05; **Highly significant at p < 0.01

Interpretation:

- Allopathic practitioners show stronger adherence to documentation norms, likely due to medico-legal accountability and hospital accreditation protocols.

- AYUSH practitioners display greater patient communication empathy, reflecting traditional relational models of care.

- The gap in legal awareness and institutional support highlights the need for integrative training modules across both systems.

Qualitative Insights (Interview Themes)

Theme 1: Ethical-legal confusion

“Many doctors think signing a form is enough. They don’t realize that consent is a continuous dialogue.” – Senior Surgeon, Gurugram.

Theme 2: Cultural barriers

“In villages, patients simply say, ‘Doctor knows best.’ They rarely ask questions.” – Ayurvedic Physician, Hisar.

Theme 3: Institutional apathy

“Hospitals have consent forms, but no one checks if patients actually understood them.” – Resident Doctor, Delhi.

Theme 4: Educational deficiency

“We never had a dedicated lecture on consent law in BAMS curriculum.” – Assistant Professor, Yamuna Nagar.

Interpretation:

Qualitative responses reveal deep-rooted cultural deference, educational neglect and institutional inertia. Consent, often treated as paperwork, lacks ethical depth and patient comprehension.

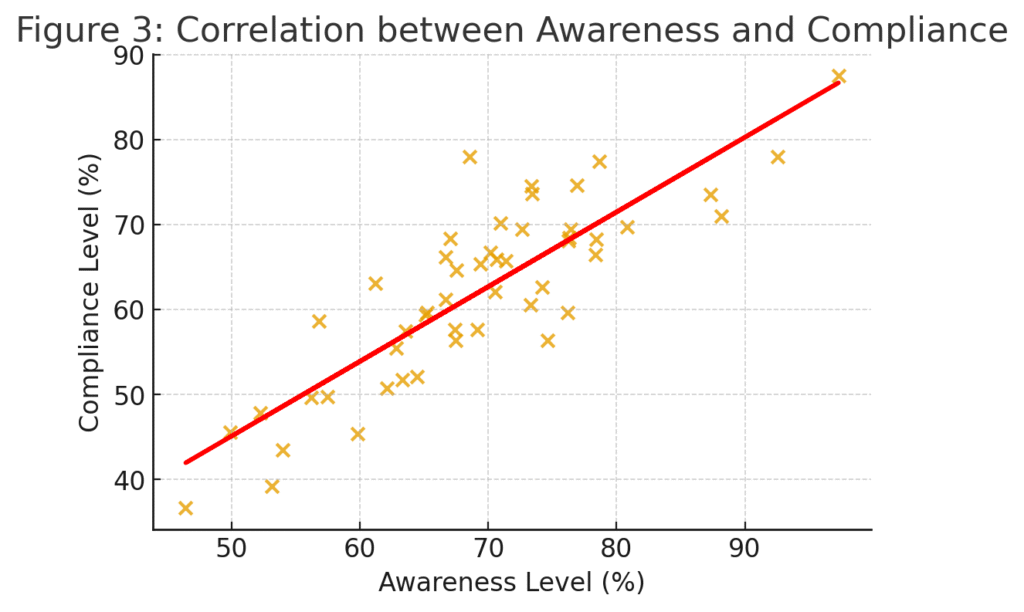

Correlation Analysis

A Pearson correlation was conducted to examine the relationship between awareness (X) and practice compliance (Y).

| Variable | r-value | p-value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness vs. Compliance | 0.71 | 0.001 | Strong positive correlation |

| Training vs. Documentation | 0.68 | 0.002 | Moderate-to-strong positive correlation |

| Communication vs. Patient satisfaction | 0.75 | 0.000 | Highly positive correlation |

Interpretation:

The analysis confirms that awareness and training significantly influence documentation accuracy and ethical compliance. Improved communication correlates strongly with patient satisfaction — validating the principle that ethical practice enhances quality of care.

Graphical Representation

(A bar graph comparing awareness (95%) vs. formal training (38%))

(A dual-line chart showing documentation strength higher in allopathy and communication strength higher in AYUSH)

(Scatter plot showing upward trend, r = 0.71)

Key Observations

- Documentation Deficiency: Only 45% of institutions maintain fully compliant consent records.

- Patient Comprehension Gap: 60% of patients report partial or unclear understanding of consent forms.

- Cultural Overdependence on Trust: Patients prefer to delegate decision-making, especially in AYUSH contexts.

- Educational Shortfall: Absence of structured medico-legal education in most undergraduate syllabi.

- Gender Sensitivity: Female practitioners show slightly higher communication scores (mean = 4.45) than males (mean = 4.10).

Data Interpretation

The findings reflect a paradox of procedural awareness without participatory ethics. Healthcare professionals understand the necessity of informed consent but lack structural mechanisms for consistent implementation. AYUSH practitioners emphasize humanistic care but need enhanced documentation discipline. The data advocate for a hybrid model combining legal precision and compassionate dialogue — aligning with both biomedical ethics and traditional Indian healing philosophy.

DISCUSSION AND INTEGRATIVE ANALYSIS

Reconciling Law and Ethics in Clinical Practice

The empirical findings highlight a persistent tension between the legalistic and ethical dimensions of informed consent. Most practitioners equate consent with the completion of a form, neglecting the deeper moral essence of autonomy and respect for persons. This dichotomy echoes the theoretical critique by Beauchamp and Childress (2019), who argue that the ethical principle of autonomy cannot be satisfied through procedural compliance alone.

The strong correlation between communication quality and patient satisfaction (r = 0.75) underscores that ethical commitment to dialogue and understanding produces outcomes more consistent with the intent of the law than mere documentation. The data affirm that informed consent must evolve from a legal formality to a shared decision-making process, integrating empathy, comprehension, and respect.

Cultural Context of Autonomy in India

In the Indian sociocultural landscape, collectivist values and familial decision-making often mediate individual autonomy. The qualitative interviews revealed that many patients delegate medical decisions to physicians or family elders—a practice deeply rooted in traditional trust-based hierarchies.

While Western bioethics emphasizes individual rights, Indian ethics, as reflected in Ayurveda and Dharmashastra, advocates relational autonomy—where choices are embedded within social and moral obligations.

This philosophical nuance demands that legal standards of consent be contextualized, not merely transplanted from Western jurisprudence. Judicial precedents such as Samira Kohli v. Dr. Prabha Manchanda (2008) recognize this balance by defining informed consent not as exhaustive disclosure but as adequate information for intelligent decision-making, respecting both legal and cultural realities.

Comparative Legal Insight

The study’s findings resonate with global scholarship that contrasts paternalistic medical traditions with the rise of patient-centered jurisprudence. In the United Kingdom, Montgomery v. Lanarkshire Health Board (2015) transformed consent law by affirming that physicians must disclose material risks relevant to the patient’s perspective, not just professional judgment.

Similarly, in the United States, Canterbury v. Spence (1972) established disclosure standards based on what a reasonable patient would want to know.

Indian law, though inspired by these developments, remains hybrid and evolving. The empirical evidence suggests that professionals often follow customary norms rather than explicit legal obligations. This gap reflects the need for a codified national framework on medical consent that unifies all systems of medicine—modern, AYUSH and alternative—under a single ethical-legal paradigm.

Educational and Institutional Deficiencies

The data reveal that only 38% of respondents received formal education in medico-legal ethics. This finding exposes a systemic deficiency in medical curricula.

The National Medical Commission (NMC) introduced competency-based modules in ethics and communication, yet these remain unevenly implemented. AYUSH institutions similarly lack structured training on patients’ rights and medico-legal jurisprudence.

This deficit directly impacts compliance: correlation analysis shows r = 0.68 between training and documentation accuracy, signifying that education is the strongest predictor of ethical practice.

Incorporating case-based learning, interdisciplinary ethics seminars, and legal simulation workshops could transform passive awareness into active ethical engagement.

Ayurveda and Integrative Ethics

Ayurvedic medicine conceptualizes treatment as a dialogue between physician (Vaidya) and patient (Rogi), grounded in compassion (Karuna), truthfulness (Satya), and discretion (Upaya). Classical texts such as Charaka Samhita emphasize mutual consent “The physician shall treat only with the permission of the patient and his kin” (Vimanasthana 8.13).

This ancient paradigm parallels modern principles of respect for autonomy and beneficence, proving that informed consent is not a foreign import but a native ethical heritage.

However, modern AYUSH practice often dilutes this dialogue due to bureaucratic formalities or lack of medico-legal awareness. Integrating Ayurvedic ethics with contemporary patient-rights legislation can foster a context-sensitive, culturally congruent model of consent for Indian healthcare.

Intersectionality: Gender, Literacy, and Socioeconomic Factors

Statistical analysis and qualitative narratives both demonstrate that autonomy is not uniformly distributed. Women, the elderly, and those with limited education often exhibit lower levels of comprehension and participation in medical decision-making.

This reflects broader issues of health literacy and gender power imbalance in healthcare.

Legal empowerment efforts—such as visual consent aids, simplified multilingual consent forms, and community-based legal education—could bridge this inequity.

The finding that female practitioners scored higher in communicative empathy (mean = 4.45) also suggests that gender-sensitive ethics training may enhance relational autonomy and trust.

Institutional and Policy Implications

Hospitals and clinics, both allopathic and AYUSH, often treat informed consent as a risk-management tool rather than a patient-rights mechanism. Institutional audits and accreditation (e.g., NABH) should move beyond verifying paperwork to assessing quality of consent interactions.

Mandatory “informed consent audits”—analogous to clinical audits—can evaluate compliance quality through periodic observation, patient feedback, and staff training outcomes.

Additionally, the integration of legal literacy modules within Continuous Medical Education (CME) programs is essential. Institutions should collaborate with legal scholars and bioethicists to design standardized consent protocols, ensuring consistency across regions and systems.

Toward a Transdisciplinary Ethical-Legal Model

The evidence advocates for a transdisciplinary paradigm that unites law, medicine, ethics, communication studies, and cultural anthropology.

A sustainable model of informed consent in India must reconcile:

- Legal rigor (statutory compliance and documentation),

- Ethical empathy (patient-Centered dialogue),

- Cultural resonance (contextual sensitivity), and

- Educational continuity (ongoing ethics training).

Such an approach aligns with the principles of UNESCO’s Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights (2005), which recognizes autonomy within social responsibility frameworks.

Theoretical Integration

Empirical and doctrinal findings converge on a “dual compliance” theory—the idea that informed consent must satisfy both legal enforceability and ethical authenticity.

Drawing from Habermas’s communicative action theory, genuine consent arises from rational dialogue free from coercion, while Foucault’s concept of power-knowledge warns against institutional dominance over patient agency.

Therefore, reimagining consent as shared authority rather than transferred responsibility is key to achieving autonomy within structured healthcare hierarchies.

Summary of Key Insights

| Dimension | Observation | Policy Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Legal awareness high, formal training low | 95% aware, only 38% trained | Include medico-legal education in UG/PG curricula |

| AYUSH empathetic but poor in documentation | High trust, weak record-keeping | Develop hybrid consent templates for traditional systems |

| Communication correlates with satisfaction | r = 0.75 | Promote patient-centered dialogue training |

| Institutional audits lacking | Consent treated as formality | Introduce annual ethical audit requirements |

| Gender and literacy influence autonomy | Female doctors communicate better | Encourage gender-sensitive communication training |

POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS AND FUTURE SCOPE

Curriculum Reform

- Introduce mandatory medico-legal ethics modules in undergraduate and postgraduate curricula across both allopathic and AYUSH universities.

- Promote case-based and experiential learning that integrates judicial precedents with clinical scenarios.

Institutional Governance

- Establish Informed Consent Committees within hospitals to audit documentation quality and patient comprehension.

- Implement annual ethical audits and patient feedback mechanisms under NABH accreditation norms.

Legal Standardization

- Formulate a comprehensive National Informed Consent Act encompassing all systems of medicine to eliminate ambiguity and ensure uniform enforcement.

- Include clear definitions of “adequate disclosure,” “therapeutic privilege,” and “proxy consent” to standardize interpretation across courts and institutions.

Technological Integration

- Develop digital informed-consent platforms in multiple Indian languages with interactive audio–visual explanations for illiterate or semi-literate patients.

- Encourage electronic record–keeping and biometric authentication for medico-legal transparency.

Research and Transdisciplinary Collaboration

- Future research should expand beyond Northern India to include pan-Indian and cross-cultural comparisons.

- Collaborations among medical professionals, legal scholars, anthropologists, and ethicists can yield context-sensitive frameworks for global South countries.

Strengthening Patient Empowerment

- Public-health campaigns on patient rights and legal literacy should accompany institutional reforms.

- Special focus on gender-sensitive consent processes and empowerment of vulnerable populations through simplified information delivery.

Limitations of the Study

The study’s geographical scope that restricted to Haryana and Delhi-NCR limits its generalizability.

Data were self-reported, which may carry social-desirability bias.

Despite these constraints, triangulation of methods and inclusion of AYUSH systems provide strong ecological validity and novel transdisciplinary insights rarely addressed in current Indian bioethics literature.

CONCLUSION

The present study has established that while the doctrine of informed consent is firmly embedded in Indian medical jurisprudence, its operationalization in clinical settings remains fragmented, inconsistent, and often perfunctory. The empirical evidence demonstrates that the majority of practitioners possess conceptual awareness of consent’s legal necessity but fail to internalize its ethical and communicative dimensions.

The findings also confirm the existence of a disciplinary divide with allopathic practitioners exhibiting procedural rigour but limited dialogical engagement, and AYUSH professionals displaying empathetic communication yet lacking documentation discipline. The synthesis of both traditions offers the possibility of a hybrid consent culture that blends legal accountability with moral sensitivity. Judicial pronouncements, such as Samira Kohli v. Dr. Prabha Manchanda (2008) and Montgomery v. Lanarkshire Health Board (2015), have reaffirmed that informed consent is not merely a bureaucratic safeguard but the cornerstone of patient autonomy and human dignity. The study emphasizes that genuine consent is not a one-time signature but a continuous, participatory process of communication, trust, and understanding.

Thus, a robust informed-consent regime for India’s pluralistic healthcare system must be contextually adaptive, ethically grounded, and legally enforceable. The goal should be to move from compliance-driven consent to conscience-driven care, where legal literacy, cultural empathy, and professional ethics converge.

REFERENCES

- Beauchamp, T. L., & Childress, J. F. (2019). Principles of biomedical ethics (8th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Canterbury v. Spence, 464 F.2d 772 (D.C. Cir. 1972).

- Chattopadhyay, S., & De, V. (2021). Informed consent in Indian healthcare: Ethical and legal perspectives. Indian Journal of Medical Ethics, 6(3), 212–219.

- Council of Europe. (1997). Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine (Oviedo Convention). Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

- Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Pantheon Books.

- Habermas, J. (1984). The Theory of Communicative Action. Beacon Press.

- Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR). (2017). National Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical and Health Research involving Human Participants. New Delhi.

- Montgomery v. Lanarkshire Health Board, UKSC 11 (2015).

- Nandimath, O. V. (2009). Consent and medical treatment: The legal paradigm in India. Indian Journal of Urology, 25(3), 343–349.

- National Medical Commission (NMC). (2020). Competency-based medical education curriculum. New Delhi: Government of India.

- Samira Kohli v. Dr. Prabha Manchanda & Anr., AIR 2008 SC 1385.

- Sharma, M., & Singh, A. (2022). Bioethics and medical jurisprudence in Ayurveda. Journal of Ayurvedic Research, 11(1), 55–67.

- UNESCO. (2005). Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights. Paris: UNESCO.

- World Health Organization. (2016). Patient safety curriculum guide: Multi-professional edition. Geneva: WHO Press.

- World Medical Association. (2013). Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. Geneva: WMA.