Abstract

The article examines the interplay between legal reforms and the realities of access to justice in rural Kerala by adopting both doctrinal and empirical approaches. Drawing on statutory developments such as the Kerala Land Reforms Act, Panchayat Raj Act, and the Gram Nyayalayas Act, alongside original fieldwork from Kuttanadu, it reveals critical gaps between legal ideals and their social implementation. The research underscores that despite progressive legal frameworks, rampant legal illiteracy, administrative inertia in legal aid, and the dominance of politically mediated dispute resolutions perpetuate exclusion for the most marginalized.

The article’s multidisciplinary lens exposes how formal guarantees of justice often fail to penetrate entrenched hierarchies, with informal power structures – especially local political leaders – serving as both gatekeepers and barriers. By integrating legal doctrine, sociological theory, and firsthand data, the study advocates for localized legal literacy, independent paralegal networks, and empirical monitoring to bridge the justice gap. The findings challenge both scholars and policymakers to transcend the boundaries of law in books, urging sustained, community-oriented reform that aligns legal empowerment.

“Justice should not depend on geography. Rural communities deserve the same access to fairness, protection, and legal support at anyone, regardless of where they live”1

Introduction

Access to justice is a foundational requirement for social inclusion and equitable development, both in legal doctrine and public policy2. Kerala, known for its progressive social metrics and history of mass mobilization, has implemented pioneering legal and policy reforms to address rural injustices3. Yet, these advances have not always translated into equal benefit for all sections of its rural population, particularly among historically marginalized groups4. Persistent reliance on informal adjudication and political mediation points to the limits of legal institutions in bridging the justice gap on the ground5. Empirical evidence from Kuttanadu underlines a stark disconnect: despite ambitious reforms, legal illiteracy, administrative inertia, and sociopolitical exclusion curtail access to effective remedies for many villagers. This article adopts a multidisciplinary approach, integrating doctrinal research, empirical observation, and sociological insight to illuminate the complex relationship between legal reform, access to justice, and social inclusion6. By examining both the structural achievements and persistent shortcomings of Kerala’s legal framework, the study reveals avenues for future reform and Justice delivery optimization7.

Legal and Policy Framework for Rural Justice in Kerala

Statutory advances in Kerala have sought to transform the legal landscape for rural citizens8. The Kerala Land Reforms Act, 1963, was a cornerstone in redistributing land and abolishing feudal tenures, dramatically shifting patterns of rural power and ownership. The Kerala Panchayat Raj Act, 1994, decentralized authority and dispute resolution, embedding governance at the village level to improve responsiveness and accountability. The Forest Rights Act, 2006, aimed to recognize and protect the rights of scheduled tribes and forest dwellers to traditional lands, combating long-standing exclusion. The Gram Nyayalayas Act, 2008, established local courts to adjudicate minor civil and criminal cases swiftly and affordably, promising to reduce the distance and cost barriers that historically deterred rural litigants. Finally, the Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987, institutionalized free legal aid for the indigent, women, and marginalized communities, underlining the importance of state-supported representation9. Although each statute was tailored to address specific deficits in rural justice, considerable gaps in practical access, procedural clarity, and public awareness remain10. The continued evolution of these frameworks reveals both the ambition of Kerala’s legal architecture and the difficulties of institutionalizing inclusive justice11.

Doctrinal, Sociological, and Empirical Approaches

A nuanced understanding of rural justice requires integrating doctrinal legal research with empirical field data and sociological perspectives. In doctrinal terms, access to justice is enshrined in the Constitution of India and is affirmed by a body of case law that frames it as a substantive right12. In the Indian context, access to justice is directly grounded in Articles 14, 21, and 39A of the Constitution, which guarantee equality before the law, the right to life and personal liberty, and free legal aid to ensure that justice is not denied to any citizen by reason of economic or other disabilities13.

The landmark Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala case introduced the “Basic Structure Doctrine,” protecting fundamental justice, equality, and access as unamendable constitutional features14. In rural Kerala, this doctrine safeguarded the core of land reform and social justice statutes. Also pertinent is Kunnathat Thathunni. Moopil Nair v. State of Kerala, where arbitrary land taxation was struck down for violating equality under Article 14, upholding the rule that land reforms must respect constitutional limits on state power15. For gender justice and property rights, Vineeta Sharma v. Rakesh Sharma is a leading case, applied by the Kerala High Court to secure equal inheritance for daughters, overriding state law exclusions16.

However, legal theory alone cannot fully account for how rules operate within social hierarchies and community interactions, particularly in the rural context. Sociologists have observed that law in rural India routinely intersects with informal systems – such as panchayat forums and political mediation – that effectively wield power over participants’ lives. The interface between law and rural society is well theorized by legal sociologist Marc Galanter, who argued that “Justice in Many Rooms” – a plural legal order – often supplants formal courts when legal literacy or trust in state law is low (Justice in Many Rooms: Courts, Private Ordering and Indigenous Law, 1981).

Pierre Bourdieu’s theory of “Legal Field” explains how social capital and local elite power shape the access and operation of law in practice (The Force of Law: Toward a Sociology of the Juridical Field, 1987). In the Indian agrarian context, writers such as R.E. Franke and B.H. Chasin, in Kerala: Radical Reform As Development in an Indian State (1994), show that true inclusion comes not merely from statute but from transformation of village-level relationships and institutional engagement.

Legal pluralism is explicit in Kerala, where formal statutes coexist with entrenched traditions of party-based negotiation and community-led settlement17. Thus, this article grounds its analysis in both statutory review and direct observation, informed by fieldwork in Kuttanadų as well as secondary literature on rural legal practices in Kerala. Such a multidisciplinary approach is crucial for uncovering not just the de jure framework, but also the de facto experiences of those the law intends to protect.

Empirical Observations from Kuttanadu

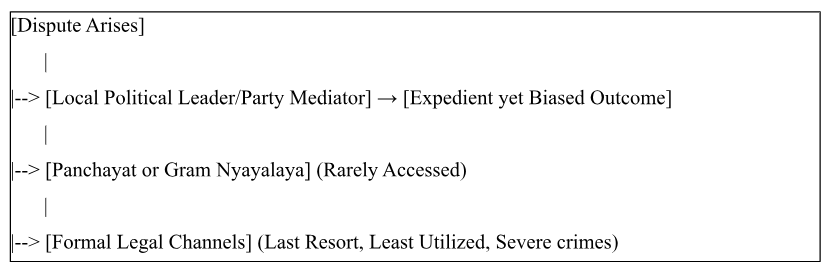

Field research in the Kuttanadu region highlights significant discrepancies between legislative ideals and empirical realities. Interviews indicate that a majority of villagers were unfamiliar with statutory rights conferred under reforms such as the Land Reforms Act. The local political party leaders, particularly from the Communist Party, are the dominant adjudicators for civil and petty criminal disputes. Their role as informal intermediaries is so prevalent that village residents routinely bypass formal legal institutions entirely in favor of decisions made within party frameworks. These leaders enjoy both social authority and organizational infrastructure, enabling them to resolve or suppress conflicts swiftly, though with a degree of bias related to party affiliation and local hierarchy.

Bias is pervasive in these settings, as party loyalty, social standing, and personal influence shape outcomes more than neutral legal principles. Administrative visits to the Taluk Legal Services Center (TLSC) in Ramankary uncovered further weaknesses: legal literacy sessions are sporadic, coverage is inconsistent, and coordination with local panchayats is frequently derailed. Regarding legal services, the panchayat-level “clinics” are best understood as Lok Adalats or rural alternative dispute forums, meant to provide accessible dispute resolution as envisaged under the Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987.

However, these clinics can only be conducted if the panchayat reports pending cases Due to poor communication of an incentive to under-reporting disputes, many panchayats claim there are “no cases,” thus blocking the Taluk Legal Services Centre (TLSC) from organizing clinics locally. Further, para legal volunteers bear the statutory duty to inform the TLSC about where and when legal awareness classes and clinics are required. Field interviews demonstrate that because volunteers do not reliably pass on this information, the TLSC is often unable to conduct legal literacy drives in the villages most in need.

This systemic gap perpetuates legal illiteracy and strengthens the hold of political and informal mechanisms over rural justice. These findings mirror broader studies that document the underperformance of legal aid outreach for rural women, Dulits, and tribal communities. The cumulative impact is a justice system underutilized by those most in need of protection, cementing patterns of exclusion instead of facilitating inclusion and development18.

Diagram 1: Dispute Resolution Process in Kuttanadu

Land Reform, Panchayat Raj, and the Changing Rural Order

The Kerala Land Reforms Act, lauded as among India’s most radical, fundamentally shifted agrarian relations by granting thousands of tenants and agricultural laborers secure title19. However, empirical reviews indicate that celling-surplus land was frequently of poor quality or inaccessibly located, and loopholes enabled larger holdings to remain with elite landowners20. While the number of landless fell sharply in the decades following implementation, the most marginalized communities, particularly Dalits and Adivasis, were most likely to be excluded or to receive insufficient holdings.

The Panchayat Raj Act, meanwhile, enhanced democratic participation, enabling local resource allocation and decentralized dispute resolution. Where panchayats were well resourced and community-engaged, they provided an important forum for Justice and redress. Yet, panchayats themselves can be dominated by partisan interests or local elites, sometimes replicating rather than dismantling rural hierarchies.

These twin reforms illustrate the complexity of translating statutory equity into widespread, durable changes in status and power relationships across Kerala’s rural landscape. Kerala’s legal reforms, fortified by robust constitutional safeguards and by an activist judiciary (e.g. Kesavananda Bharati, Vineeta Sharma), set a high doctrinal bar. Yet, as Galanter and Franke observe, and as Kuttanadu’s persistent reliance on Communist Party mediation attests, everyday justice for marginalized rural groups often turns more on social context than formal law.

The Gram Nyayalayas Act: Promise and Shortfall

The Gram Nyayalayas Act, enacted to bring justice closer to the rural populace, is an instructive case of both innovation and inertia21. The design called for local courts to operate within communities, employing simplified procedures and enabling litigants to avoid travel to distant district courts. However, fieldwork and independent assessments show only a limited functional presence of Gram Nyayalayas across Kerala, with community awareness extremely low. Bar association resistance, insufficient judicial appointments, and lack of publicity have all slowed uptake.

Interviews in Kuttanadu revealed not a single respondent had direct experience with Gram Nyayalayas, highlighting the need for targeted education and administrative support. Where Gram Nyayalayas were active, cases were resolved more quickly, but unresolved barriers-such as irregular sittings and failure to publicize court dates – remained problematic. The shortcomings of this Innovation illustrate the risk of launching reforms without robust mechanisms for local engagement and feedback.

Legal Aid, Literacy, and Administrative Capacity

The Legal Services Authorities Act mandates free legal aid and outreach for specified groups. Yet its full promise remains unrealized in many rural locale22. Field and administrative data show that legal aid clinics are either undersupplied or inconsistently accessible, with one clinic now serving as many as fifteen villages. Para-legal volunteer programs, theoretically robust, often founder due to uneven training, volunteer attrition, and poor alignment with community needs. Administrative reluctance to intervene – evident in common refusals to set up clinics based on “no case pending” rationales-exacerbates the exclusion of under-served areas.

Gender and caste continue to influence who receives aid and who dares to file claims: studies in Malappuram show women’s legal clinics increase access and reporting, but reach remains highly uneven. Institutionalizing ongoing legal literacy, especially through localized and participatory formats, is essential for converting statutory rights into practical remedies among marginalized groups.

Graph 1: Decline in Legal Aid Clinics and Coverage (2022-2024)

Year | Functioning Clinics | Avg. Villages per Clinic |

2022 | 101 | 9 |

2024 | 66 | 15 |

Gender, Caste, and the Experience of Rural Justice

Kerala’s reputation for progressive gender and caste representation does not always include its most vulnerable rural inhabitants. Despite robust rights frameworks, Dalit, tribal, and female litigants are far less likely to access courts and more likely to settle for informal justice mediated by patriarchal or party elites. In family, property, and personal law disputes, women in Kuttanadu cited both social stigma and lack of legal knowledge as primary deterrents to formal redress. Representation among district judges has improved but remains limited at higher court and administrative levels, particularly for Scheduled Tribes.

Gender-targeted legal literacy and empowerment campaigns increase reporting, but are highly dependent on funding continuity and collaboration with local institutions. True Inclusion thus requires not only statutes, but also persistent support, advocacy, and community transformation.

Alternative Dispute Forums and Digital Innovation

Lok Adalats, village courts, and mediation forums have shown potential to resolve disputes speedily and cheaply, particularly for family and land cases. The spread of digital innovation – such as e-filing and remote hearings for Permanent Lok Adalats – has further reduced access barriers for rural claimants, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic and natural disasters. Yet, digital and alternative dispute solutions are unlikely to reach the most marginalized without targeted interventions in technological literacy and infrastructural support. In this context, digital strategies should supplement, not supplant, persistent investment in in-person outreach and local legal education.

Barriers to Effective Justice Delivery

Despite ambitious reforms, the justice gap in rural Kerala is underpinned by intersecting barriers Legal illiteracy remains widespread, shaped by education deficits, social stigma, and linguistic differences. Political mediation, while sometimes efficient, entrenches local fiefdoms and hinders impartial justice, especially where party and social hierarchies converge. Administrative constraints-insufficient funding, lack of coordination among legal aid agencies, and limited data- driven oversight-stunt innovation and frustrate community trust. Where reforms remain underpublicized or poorly monitored, vulnerable populations inevitably fall through the cracks23. Structural inclusion will require confronting and overcoming each of these dimensions, not just relying on new legislation.

Recommendations

Legal and social inclusion in rural Kerala is not simply a function of what is legislated, but of how laws are delivered, known, and experienced:

- Localized Legal Literacy: Develop sustained, community-tailored legal literacy programs in local languages, using street theatre, trained paralegals, and youth groups to enhance reach and impact

- Paralegal Networks & Volunteer Empowerment: Invest in independent paralegal networks, with adequate training and transparent selection, to bridge the gap between formal legal systems and rural users.

- Administrative Reform: Clarify roles, responsibilities, and reporting for legal aid authorities; enforce performance metrics and community feedback mechanisms to ensure regular operation of clinics and workshops.

- Inclusive ADR and Digital Solutions: Ensure alternative dispute mechanisms and digital resources are accessible, unbiased, and monitored for equity in outcome, with periodic review by independent bodies

- Continuous Empirical Monitoring: Institutionalize mechanisms for collecting user feedback and outcome data, using these to adapt policy and practice.

- Equity in Representation: Prioritize representation of women, Scheduled Castes, and Scheduled Tribes at all levels of rural justice administration and support their participation in dispute forums.

Conclusion

The legal reforms implemented in Kerala stand as a testament to the power of legislative Innovation, constitutional foresight, and the enduring legacy of social movements in Indian democracy. However, as this study demonstrates, the translation of those reforms-from constitutional text and statutory design to the day-to-day realities of rural justice-remains profoundly incomplete.

Doctrinal analysis reveals that the constitutional commitments articulated in Articles 14, 21, and 39A, and defended through leading case law such as Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala and Kunnathat Thathunni Moopil Nair v. State of Kerala, have enabled Kerala to establish a scaffolding for legal empowerment that is both robust and exemplary within the Indian context. The statutory architecture-encompassing the Kerala Land Reforms Act, The Panchayat Raj Act, The Gram Nyayalayas Act, and the Legal Services Authorities Act-has, in principle, reengineered social and legal relations for historically excluded groups, particularly within rural agrarian society.

References

- Constitution of India art. 14, art. 21, art. 39A.

- Kerala Land Reforms Act, No. 1 of 1964, INDIA CODE (Ker.).

- Kerala Panchayat Raj Act, No. 13 of 1994, INDIA CODE (Ker.).

- The Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, No. 2 of 2007, INDIA CODE (India).

- Gram Nyayalayas Act. No. 4 of 2009, INDIA CODE (India).

- Legal Services Authorities Act, No. 39 of 1987, INDIA CODE (India).

- Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala. (1973) 4 S.C.C. 225 (India).

- Kunnathat Thathunni Moopli Nair v. State of Kerala, A.LR. 1961 S.C. 552 (India).

- Vineeta Sharma v. Rakesh Sharma, (2020) 9 S.C.C. 1 (India).

- R.W. Franke & B.H. Chasin, Kerala: Radical Reform as Development in an Indian State (2d ed. 1994).

- Marc Galanter, Justice in Many Rooms: Courts. Private Ordering and Indigenous Law, 19 J. LEGAL PLURALISM & UNOFFICIAL L. 1 (1981).

- Pierre Bourdieu, The Force of Law: Toward a Sociology of the Juridical Field, 38 HASTINGS L.J. 805 (1987).

- Niraja Gopal Jayal et al., Local Governance in India: Decentralization and Beyond (2006).

- T.M. Thomas Isaac & R.W. Franke, Local Democracy and Development: People’s Campaign for Decentralized Planning in Kerala (2000).

- Upendra Baxi, The Crisis of the Indian Legal System (1982).

- Ranabir Samaddar, The Politics of Autonomy. Indian Experiences (2005).

- Prakash Arya, Irrational Land Distribution among Dalits and Tribes: An Enigma Before Kerala Economy, & INT’L J. DEV. RES. 25452 (2018).

- S. Sen & S. Sreekumar, Gendered Justice and Legal Empowerment in Rural Kerala, 44(2) INDIAN J. GENDER STUD. 113 (2023).

- Malappuram DLSA, District Legal Empowerment Report (2023) (India).

- Kerala State Legal Services Authority (KELSA), Annual Report (2023) (India).

- India Justice Report, Kerala Chapter (2025) (India).

- National Legal Services Authority, Lok Adalat Dispute Resolution Reports (2023) (India).

- National Law School of India University, Access to Justice and Empirical Baselines (2021) (India).

- United Nations Development Programme, Access to Justice Practice Note (2004).

Footnotes

- Fact Sheet: Access to Justice is Rural Access, U.S. Department of Justice (2025) ↩︎

- United Nations Development Programme, Access to Justice: Practice Note (2004) ↩︎

- Kerala Land Reforms Act, 1963. ↩︎

- Arya, P., Irrational Land Distribution among Dalits and Tribes: An Enigma Before Kerala Economy, Int’l J. of Development Research (2018) ↩︎

- Jeffrey, R., Politics, Women and Well-Being: How Kerala Became “A Model” (1992). ↩︎

- Chatterjee, P., The Politics of the Governed (2004). ↩︎

- Law Reforms Commission Kerala, Vol. I, 2009. ↩︎

- Kerala Land Reforms Act, 1963. ↩︎

- Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987. ↩︎

- Franke, R.W. & Chasin, B.H., Kerala: Radical Reform As Developmet in an Indian State (2nd ed. 1994). ↩︎

- Kerala Land Reforms Act, 1963. ↩︎

- Law Reforms Commission Kerala, Vol. I, 2009. ↩︎

- Constitution of India, Arts. 14, 21, 39A. ↩︎

- Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala, (1973) 4 SCC 225 ↩︎

- Kunnathat Thathunni Moopil Nair v. State of Kerala, AUR 1961 SC 552 ↩︎

- Vineeta Sharma v. Rakesh Sharma, (2020) 9 SCC 1 ↩︎

- Arya, P., Irrational Land distribution among Dalits and Tribes: An Enigma Before Kerala Economy, Int’l J. of Development Research (2018) ↩︎

- Franke, R.W. & Chasin, B.H., Kerala: Radical Reform As Development in An Indian State (2nd ed. 1994). ↩︎

- Kerala Land Reforms Act, 1963. ↩︎

- Arya, P., irrational Land Distribution among Dalits and Tribes: An Enigma Before Kerala Economy, Int’l J. of Development Research (2018) ↩︎

- Law Reforms Commission Kerala, Vol. I, 2009 ↩︎

- Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987. ↩︎

- Arya p., Irrational Land Distribution among Dalits and Tribes: An Enigma Before Kerala Economy, Int’l J. of development Research (2018). ↩︎