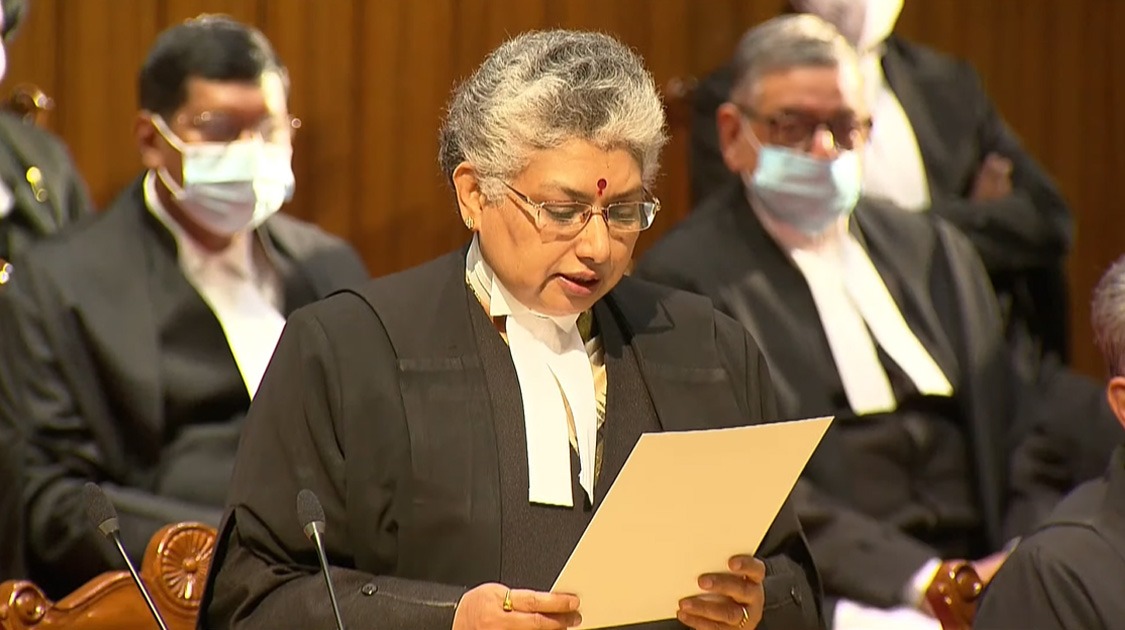

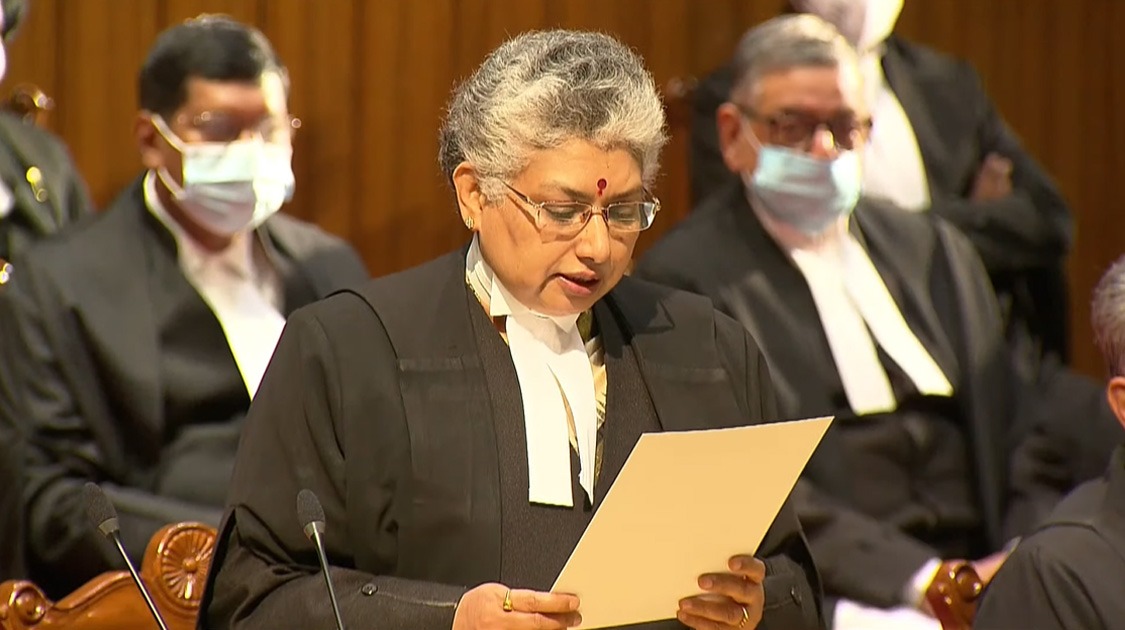

Constitution Is Stronger Now Because Of Kesavananda Bharati Judgement: Justice BV Nagarathna

Supreme Court judge Justice BV Nagarathna said that the Constitution of India is stronger now because of the Kesavananda Bharati judgement, which laid down the doctrine of basic structure.

Justice B.V. Nagarathna was delivering the Chief Justice KK Usha Memorial Lecture on the topic ‘Transformative Constitutionalism‘ organised by the Kerala Federation of Women Lawyers at the High Court of Kerala.

The views of Js. Nagarathna echoed in light of the current debate going on between the protection of judicial independence and the un-restrictive Constitutional Amendment power of the Parliament.

Recently the Vice-President of India Jagdeep Dhankar while addressing the 83rd All India Presiding Officers Conference, questioned the validity of the landmark Kesavananda Bharti judgement of 1973 that gave birth to the Basic Structure doctrine.

While addressing the Conference, he said that

“In 1973, a wrong precedent (galat parampara) started.

“In 1973, in the Kesavananda Bharati case, the Supreme Court gave the idea of basic structure saying Parliament can amend the Constitution but not its basic structure. With due respect to the judiciary, I cannot subscribe to this.”

While again criticising the scrapping of the National Judicial Appointment Commission (NJAC), he said that the Basic Structure doctrine est. via Kesavananda Bharti case put a limit on the Constitutional Amendment power of the Parliament which is against the principle of parliamentary democracy.

To contrast in praise of Kesavananda Bharti’s judgement and Doctrine of Basic Structure, the CJI D Y Chandrachud while delivering Nani A Palkhivala Memorial Lecture called the basic structure doctrine “a North Star that guides and gives a certain direction to the interpreters and implementers of the Constitution when the path ahead is convoluted.”

Kesavananda Bharti Case

The judgement was in succession to 1969, Golak Nath case in which the Hon’ble Supreme Court kept Part III of the Constitution out of the purview of Ar 368 of the Constitution. It specifically placed a complete restriction on amending the power of the Parliament regarding the Fundamental Rights enshrined in Part III of the Constitution in India.

In its contrast, in the Kesavananda Bharti case, the Supreme Court of India laid down the principle that Parliament can amend any part of the Constitution including Part III but without compromising on the Basic Structure of the Constitution. However, no proper definition of what constitutes the basic structure of the Constitution is still in abeyance.

Through its various judgements, the Supreme Court has added various dimensions and elements to its sui generis concept of basic structure like Supremacy of the Constitution, Secularism, Judicial Independence, Judicial Review, Doctrine of Separation of Power, Federal polity, Limited power of the Parliament to amend the Constitution, System of Parliamentary Democracy, Doctrine of Rule of Law, Principle of Right to Equality etc.

Political Reaction to the Judgement

In reaction to the 1973 judgement, the Govt. of Indira Gandhi elevated Js. A.N. Ray to the office of CJI by circumventing the seniority principle as there were already 3 SC judges senior to Js. Ray. Many new judicial appointments were also made, and, in 1975, with eight new judges on the bench and an emergency having been declared, CJI A N Ray set up a 13 judges Bench to review the Kesavananda Bharti case judgement.

However, CJI Ray had to unilaterally dissolve the Bench as no review application had been filed against the judgement.

Importance of the Kesavananda Bharti judgement

The Basic Structure Doctrine laid down in the Kesavananda Bharti case proved to be an important tool in the hands of the judiciary that helped it to keep a check on the arbitrary legislation done by the Parliament and Executive.

The same can be evident from the following judgements-

Raj Narain Case, 1975

In this case, the SC applied the theory of basic structure and struck down Clause(4) of Article 329-A, which was inserted by the 39th Amendment in 1975 on the grounds that it was beyond the Parliament’s amending power as it destroyed the Constitution’s basic features.

The 39th Amendment Act was passed by the Parliament during the period of National Emergency that placed the election of the President, the Vice President, the Prime Minister and the Speaker of the Lok Sabha beyond the scrutiny of the judiciary.

Minerva Mills Case, 1980

In this case, the Court added two features to the list of basic structure doctrine: Judicial Review and Balance between Fundamental Rights and DPSP.

The judges ruled that a limited amending power itself is a basic feature of the Constitution.

Waman Rao case, 1981

Again reiterating the basic structure principle, the Hon’ble SC held that amendments made to the 9th Schedule until the Kesavananda judgement are valid, and those passed after that date can be subject to scrutiny.

Indra Sawhney case, 1992

While upholding the 27% reservations for the Other Backward Classes (OBCs) with certain exceptions the Hon’ble SC added the Rule of Law to the list of Basic structure.

S R Bommai Case, 1994

In this case, the SC held that policies of a state government directed against an element of the basic structure of the Constitution (Federal Polity) would be a valid ground for the exercise of the Emergency power by the Central Govt. under Article 356.

Conclusion

The policy laid down under the basic structure doctrine by the SC is all meant to put reasonable restrictions on the arbitrary legislation passed by the Parliament. The doctrine has been proved as a valuable tool to keep a check on the Constitutional Amendment power of the Parliament provided under Ar 368.

However, in its contrast, an alternative thought is also gaining ground that since constitutional amendments have been keeping alive the spirit of the Constitution, the Doctrine of Basic Structure also needs to undergo regular changes as per the changing spirit and aspirations of the society.