the-indian-education-system-explained

Introduction

Dalits have long been marginalized and have only grudgingly been accepted in the history of India. They first came into the limelight when Mahatma Gandhi used the term ‘Harijans’ meaning children of God to refer to the ‘untouchables’ and established the Harijan Sevak Sangh to eradicate untouchability in India. The word ‘Dalit’ literally meaning ‘broken’ or scattered is used to refer to the lowest stratum of the castes and are considered to be outside the caste system. Human rights are protected by the constitutions and legal systems of nations with established constitutions, including India. However, its pleasure is severely limited by the economic, political, and social position of a group of individuals, resulting in unequal treatment of the subjects. Stigma accompanies a person from birth to death, influencing all aspects of life including school, housing, employment, access to justice, and political engagement. A brief historical background tracing the origins of Dalits in India is important before getting into their current situation, government initiatives, how human rights of the Dalits are violated and public initiatives to overcome this discrimination.

Tracing The History

The origins of Dalit oppression can be traced back to the inception of the caste system in India. The tenth Rigveda describes the creation of the four castes from Brahma (the creator), with Brahmins emerging from his head, Kshatriyas from his arms, Vaishyas from his thighs, and Shudras from his feet. Dalits were deemed so impure that they were excluded from the caste system entirely. Birth determined one’s caste, which in turn dictated whom they could marry and the occupations they could pursue.

Historically, Dalits were compelled to engage in occupations considered ritually impure by higher castes, such as handling carcasses, managing human waste, street sweeping, and cobbling. They endured mistreatment from those of higher castes, especially Brahmins, who refused to consume food prepared by Dalits, share wells with them, or even bathe if touched by a Dalit’s shadow. Dalit women often suffered sexual exploitation by men from higher castes.

Challenging the caste system resulted in severe punishments, including public humiliation, physical abuse, sexual assault, and even death. In the 13th century CE, with the arrival of Islam in India, many ‘untouchables’ and lower-caste individuals converted to Islam as a means of escape.

During the struggle for Independence, two distinct approaches emerged to uplift Dalits. Mahatma Gandhi advocated for retaining the caste system while eliminating the stigma and practices of untouchability. In contrast, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar championed the complete abolition of the caste system. He also advocated for separate legal and constitutional recognition for Dalits and eventually converted to Buddhism, a path followed by a significant number of his followers.

Laws And Provisions

After India’s Independence, the government introduced various measures to address the disparities between oppressed and privileged castes. The Indian Constitution, which was enacted in 1950, upholds the principles of equality, freedom, justice, and human dignity. It mandates both state and central governments to provide special safeguards for members of scheduled castes, elevate their standard of living, and ensure their equality with others.

In pursuit of these goals, the Indian government has adopted a two-pronged approach to reduce the socio-economic gap between the scheduled caste population and the national average. The first aspect involves implementing, enforcing, and monitoring relevant legal provisions through regulatory measures. The second aspect focuses on enhancing the self-sufficiency of scheduled castes through financial support for self-employment ventures and development programs aimed at improving education and skills.

Key Fundamental Rights enshrined in Articles 14, 15, 16, 17, 19, 21, 21(A), 23, and 24 play a crucial role in ensuring that individuals have access to social and economic rights. (Bornare, 2019)

- Article 14 Equality before law was an important step in ensuring that all people are dispensed justice and are under equal protection of the law irrespective of their background.

- Article 15 prohibits discrimination based on religion, caste, sex, birth place. The state has the authority to enact additional safeguards, such as affirmative action programs, to address the condition of “scheduled castes.” The term “scheduled castes” refers to a list of underprivileged castes, such as Dalits, that were first recognized as eligible for government protections by the British government in 1935. The article also explicitly states that no one will be denied “access to shops, public restaurants, hotels and places of public entertainment” or “the use of wells, tanks, bathing ghats, roads and places of public resort maintained wholly or partly out of State funds or dedicated to the use of the general public.” (Bornare, 2019)

- Article 16 Equality of opportunity in matters of public employment, thus expressly allowing the State the authority to reserve government employment placements for members of castes who are underrepresented in specified areas. In accordance with this constitutional authority, the Indian government established an affirmative action program that admitted Dalits to schools and universities with lower admittance criteria, allocated Dalits 22.5 percent of all government positions, and reserved 85 of the 545 seats in Parliament for Dalits. (Bornare, 2019)

- Article 17 of the Indian constitution officially abolished untouchability and made it a punishable offence.

Certain Directive Principles of the Indian Constitution also contribute in bringing social equality and justice. (Bornare, 2019)

- Article 38 – State is under obligation to minimize the inequalities in income and endeavor to eliminate inequalities in status, facilities and opportunities amongst all people.

- Article 46 – For the promotion of educational and economic interest of Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and other weaker sections, Article 46 is important. It is the duty of state to protect these oppressed people from injustice and all forms of exploitation.

- Article 338 A Human Rights Commission was constituted under Article 338 for better protection of the rights of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribe people.

Several additional sections of Indian domestic law, in theory, both protect Dalits against caste prejudice and aid in enhancing Dalits’ socioeconomic condition.

The Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Prevention of Atrocities Act of 1989 (1989 Act) offers a comprehensive set of safeguards for Dalits. This legislation criminalizes actions such as compelling Dalits to consume inedible or repugnant substances, forcing them to disrobe or engage in public nudity, or subjecting them to bonded labor. It also provides protection against false legal charges, sexual exploitation, and interference with their voting and property rights. Those found guilty of violating the 1989 Act can be penalized with fines and imprisonment, and repeat offenders may face a minimum one-year jail term for each offense. The Act further mandates the establishment of Special Courts by states to adjudicate cases involving Scheduled Castes. Additionally, the Act imposes penalties on public officials who fail to enforce its protections. The Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Rules of 1995 detail additional procedures that state governments must follow to investigate, prosecute, and punish violations of the 1989 Act. (Bagde, 2020)

The Employment of Manual Scavengers and Construction of Dry Latrines

(Prohibition) Act of 1993 (1993 Act) prohibits the employment of manual scavengers in the interest of human dignity and public health. Moreover, the 1993 Act prohibits the use of dry latrines, which need the use of hand scavengers to remove human waste. The 1993 Act, which applies to the states of Andhra Pradesh, Goa, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Tripura, and West Bengal, has the potential to put an end to the demeaning and exploitative practice of manual scavenging if it is enforced. (Bagde, 2020)

As an active member of The United Nations, India is bound to the provisions in The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), Human Rights Committee (HRC), etc., which aim to eradicate discrimination of any kind as well as protection of all citizens.

Societal Reality Of These Laws

The constitution has merely prescribed, but has not given any description of the ground reality. We can make a dent only if we recognize the fact that the caste system is a major source, indeed an obnoxious one, of human rights violations.

R. M. Pal, “The Caste System and Human Rights Violations”

According to the National Campaign on Dalit Human Rights (NCDHR) One crime is committed against a Dalit every 18 minutes, Six Dalits kidnapped or abducted every week, Three Dalit women raped every week, Thirteen Dalits murdered every week, Twenty- seven atrocities against Dalits every day.

Approximately 200 million people, which is more than one-sixth of India’s population, live in a precarious state, marginalized from mainstream society and facing daily threats of violence, including murder and rape. According to the Annual Report for 2017-2018 from the Department of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India, there were a total of 47,337 registered cases under the “Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989” across India. Additionally, the National Crime Records Bureau of India reports approximately 45,935 cases of violence against Dalits each year. These reports and statistics reveal that human rights abuses against Dalits remain pervasive in our society.

Many Dalit individuals, including men, women, and children, lack access to land and are forced to work as agricultural laborers, living on the edge of destitution. They struggle to provide for themselves, educate their children, and break free from cycles of debt bondage. Any attempt to challenge the established social order is met with violence or economic reprisals (Bornare, 2019).

The persistence of human rights violations against Dalits in India is closely linked to police misconduct. Local law enforcement often fails to register crimes against caste Hindus or enforce appropriate legislation designed to protect Dalits. Due to caste and gender biases or influence from powerful landlords and upper-caste politicians, the police not only allow caste Hindus to act with impunity but sometimes act as agents of powerful upper-caste groups. They detain Dalits who organize protests against discrimination and violence and punish Dalit villagers suspected of supporting militant groups.

While the Indian constitution and various laws grant Dalits certain privileges, including reservations (quotas) in education, government jobs, and government bodies, these laws have benefited only a limited number of individuals. Development programs and welfare initiatives aimed at improving the economic conditions of Dalits have had minimal impact due to a lack of political will. Dalits continue to face bondage and economic exploitation by upper-caste landowners (Human Rights Watch, 1999).

Even after fifty years of independence, it remains impossible to convince the Dalits of Dholapur district, Rajasthan, that the government has taken meaningful steps to address the violence and discrimination that have governed their lives. An upper-caste family subjected a Dalit to a brutal attack in April 1998 because he refused to sell bidis on credit to the nephew of the upper-caste village leader. This incident involved violent acts like piercing the Dalit’s nostril, threading a string through his nose, parading him around the village, and tying him to a cow post.

Discriminatory practices are not limited to society but also extend to the Indian judiciary. In July 1998, an Allahabad High Court judge had his rooms “purified with Ganga Jal” because they had been previously used by a Dalit judge. In rural areas, most Dalits live in segregated colonies separate from Hindu castes. In Tamil Nadu’s Villapuram district, for instance, an activist working with Dalit communities in 120 villages observed that all 120 villages have segregated Dalit colonies. Even basic necessities like water are segregated, with the better, thatched-roof dwellings typically found in the caste Hindu community. The state reinforces “untouchability” by providing different facilities for each colony, often offering Dalits the poorer of the two options or no facilities at all (Hanchinamani, 2001).

Case Studies

Millions of cases are available which clearly showcase the deplorable condition of Dalits and the constant abuse of their human rights. Even in the face of catastrophic events, Dalits are unable to escape unscathed. In the aftermath of the 26 December 2004 Tsunami in Tamil Nadu, Dalits found themselves denied entry from relief camps or the use of portable water tanks in case they “polluted” the water. (minority rights group, n.d.)

Covid was accompanied by a fresh wave of problems including being completely unprepared for lockdown preparations, especially due to their economic conditions. They were also blamed for spreading the virus instead of being appreciated for their frontline work as health workers. (thorat, 2022)

In a very recent case of brutality and murder in Nanguneri Town of Tamil Nadu, a teenage Dalit boy and his sister were assaulted and whipped with a sickle by his higher caste schoolmates. He used to be regularly bullied by the same classmates for being “good in his studies” despite his Dalit status. (P., 2023) (Fathima, 2023)

A case study on economic, social and cultural rights for Dalits in India was done by Ellyn Artis, Chad Doobay and Karen Lyons. The case study focused on primary education in Gujarat where they found a number of things related to discrimination in the arenas of

classroom seating, permission to participate in class activities and the receipt of lower marks for high-quality work. A very common complaint in a lot of villages was the requirement of non-Dalit teachers that Dalit students sit at the back of the classroom. They also found from many reports the high mark gap between non-Dalit and Dalit students, with Dalits faring relatively poorly.

Jagruti, a 12-year-old girl from the village of Sahpur, informed the interviewers that the instructor requires Dalit children to wait until a non-Dalit is available to pour water from several feet above them into their hands or mouths.

Six schools in the taluka, according to Sami Dalit organizers, have restrictions that keep Dalit pupils segregated from non-Dalit children at lunchtime. Such discriminatory practice does not exclude Dalit teachers. Jignasha, a Dalit teacher in the village of Kumbhana, was advised by her principal to keep her waterpot separate from the water pots of other instructors. Dalit children were also expected to perform additional cleaning responsibilities as a group, although non-Dalit children were not. (ellyn artis, 2003)

Caste And Women

Caste-based violence, more often than not, expresses itself through a gender-based weapon and this violence is not restricted to any one caste, women from all castes suffer from it. Vasanth Kannabiran and Kalpana Kannabiran’s work, titled ‘Caste and Gender: Understanding Dynamics of Power and Violence’ explores how the caste question and women’s question are intermeshed and how each of them can only be understood with reference to the other. The commentary piece elucidates on intersectionality with a major focus on the cases that took place in Tsundur, Chilakurti and Gokarajupalli.

Men demonstrate their control by humiliating women of another caste, as they regard it as attacking the ‘manhood’ of men from that caste. This is evident in the case from Chilakurti which took place on 14th August 1991. Muthamma, a woman from the Golla caste, was beaten up and paraded naked on the street by three Reddi goons. The women and men could not bear seeing this and either hid or shut their eyes. The aggressors furthered the insult by asking questions like, “Open your eyes. Are there no men amongst you?”. The incident shows how gender is defined by the capacity to aggress and appropriate the other and the structure of relations in caste society can castrate men through the expropriation of their women.

Another example of expropriation is from Orissa, when a Dalit woman was summoned for some work, she said that she would come only after her husband had eaten but this mere statement ended up getting both her and her husband beaten up and their lives were made miserable from then on. (kannabiran, September 1991).

According to Dalit activists, Dalit girls have been forced to have sex with the village landlord. In rural areas, “women are induced into prostitution (Devadasi system)., which [is] forced on them in the name of religion.” Dalit women are easy targets for any perpetrator because upper castes consider them to be “sexually available” and because they are largely unprotected by the state machinery. The Bathani Tola massacre in Bihar in 1996 epitomizes this phenomenon. (minority rights group , n.d.)

Analysis

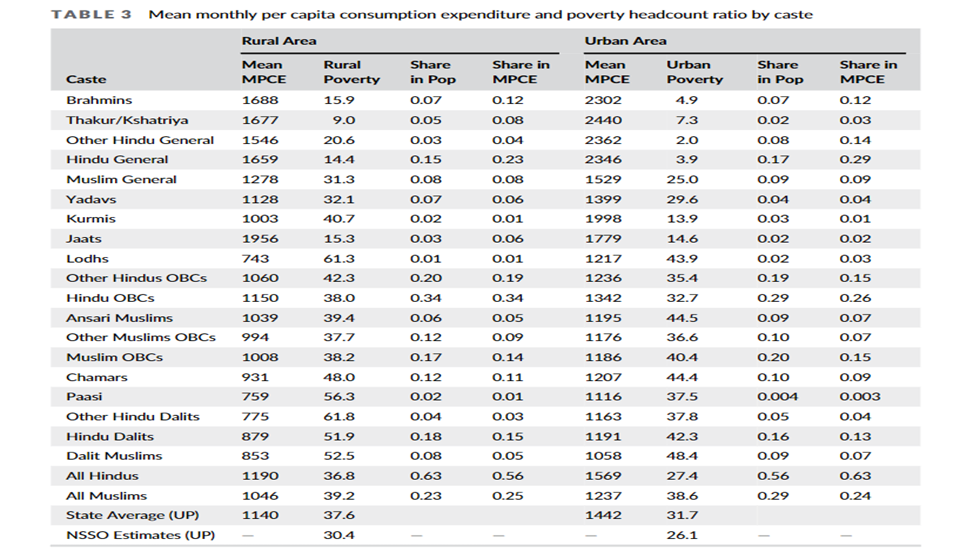

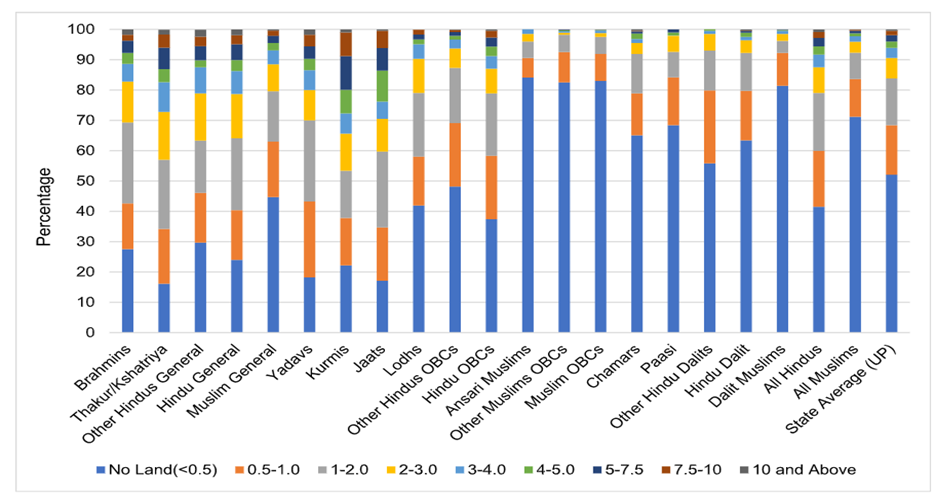

A research article, titled “Poverty, Wealth Inequality and financial inclusion among castes in Hindu and Muslim Communities in Uttar Pradesh, India” authored by Chhavi Tiwari, Srinivas Goli, Mohammad Zahid Siddiqui and Pradeep S. Salve uses data from a unique primary survey collected by the Giri Institute of Development Studies (GIDS) to assess the social and educational Status of OBCs and Dalit Muslims in Uttar Pradesh during 2014–2015. (shroff, 2022)

It has broadly categorized the economic and social status of a household into four broad domains, that is, deprivation of lifestyle, historical deprivation, household condition and wealth and deprivation in financial inclusion.

Deprivation in lifestyle: poverty and expenditure

This indicates that caste-based supremacy in social and economic activity persists in some form or another.

Land ownership and historical deprivation

Deprivation in wealth accumulation, household conditions and amenities

Conclusion: How Do We Overcome Caste-Based Discrimination

Affirmative action programs guaranteed by the constitution have positively affected the representation of Dalits in educational institutions, government posts, and elected offices. Despite this progress, Dalits remain the most disadvantaged segment of Indian society, and the stigma they experience still persists. Dalits in general continue to live in deplorable, brutal conditions. The reservation provision has been extended many times highlighting successive governments’ inability to repair decades of wrong by creating a level playing field. This also highlights the flaws in our political culture. Many politicians who ascended to power professing to promote the cause of Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, or Other Backward Classes have focused on acquiring and promoting their own wealth, rather than fighting for the public and altering the reality on the ground. (singh, 2022)

What can be done then? Making sure the laws are implemented and people who are supposed to benefit from it are able to avail those opportunities surely matters and will go a long way in helping the Dalits. Society has to change from within, as law by itself will not be able to solve the larger problem. Former President APJ Abdul Kalam stressed that to become a developed country, India must give urban facilities in rural regions (RURA) to eliminate socioeconomic inequities. Kalam stated that if the government significantly increased college seats and work possibilities, quota restrictions would be unnecessary, eliminating the issue of social tension. Authorities must also do their part to prevent prejudice, oppression, and violence, as well as prosecute violators. (singh, 2022)

Dalits have to be given the right to speak for themselves and raise their own voices instead of other people speaking over them.

References

- Bagde, U. S. (2020). Human rights perspectives of indian dalits. journal of law and conflict resolution, 26-32.

- Bornare, V. R. (2019). Human rights of dalits in india. gap interdisciplinaries .

- Deliege, R. ( september 1993). The myths of origins of the indian untouchables. royal anthropological institute of great britiain and ireland, 533-549.

- ellyn artis, c. d. (2003). economic, social ad cultural rights for dalits in india: case study on primary education in gujarat. princeton university.

- fathima, a. (2023, august 18). caste faultlines among schoolkids. Retrieved from newslaundry.com: https://www.newslaundry.com/2023/08/18/caste-faultlines-among-schoolkids-in-tn-dalit-teen-family-attacked-over-caste-identity

- gulati, a. (2018, september 11). dalit: the word, sentiment, and a 200 year old history. Retrieved from thequint.com: https://www.thequint.com/news/india/dalit-history-of-term-political-social-usage

- Hanchinamani, B. B. (2001). Human rights abuses of Dalits in india. human rights brief.

- HRW. (2007, february 13). india: ‘hidden apartheid’ of discrimination against dalits. Retrieved from hrw.org: https://www.hrw.org/news/2007/02/13/india-hidden-apartheid-discrimination-against-dalits

- human rights watch. (1999). caste violence against india’s untouchables. usa.

- Kannabiran, v. k. (september 1991). caste and gender: understanding dynamics of power and violence. economic and political weekly.

- Minority rights group . (n.d.). dalits. Retrieved from minorityrights.org: https://minorityrights.org/minorities/dalits

- NCDHR. (2018). national campaign on dalit human rights. Retrieved from ncdhr.org.in: http://www.ncdhr.org.in

- P., s. (2023, august 26). felled by caste pride in tamil nadu’s nanguneri town. Retrieved from thehindu.com: https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/tamil-nadu/felled-by-caste-pride-in-tamil-nadus-nanguneri-

- Shroff, k. (2022, may 02). what does the caste wealth gap look like in india? Retrieved from m.thewire.in: https://thewire.in/economy/what-does-the-caste-wealth-gap-look-like-in-india

- Singh, d. (2022, august 18). who is dalit or savarna? why caste system must go in totality. Retrieved from indiatoday.in: https://www.indiatoday.in/news-analysis/story/dalit-sawarn-caste-system-must-go-1989509-2022-08-18

- Slic. (2022). dalit rights initiative. Retrieved from slic.org.in: https://www.slic.org.in/initiative/dalit-rights-initiative

- Thorat, a. t. (2022, february 11). employment and the dalit equation. Retrieved from outlookindia.com: https://thewire.in/economy/what-does-the-caste-wealth-gap-look-like-in-india

- United nations . (2021, april 19). the dalit: born into a life of discrimination and stigma. Retrieved from ohchr.org: https://www.ohchr.org/en/stories/2021/04/dalit-born-life-discrimination-and-stigma