“MARITAL RAPE” A CRIME OR A DESIGNED SOCIAL CONSEQUENCE?

Chapter 1- INTRODUCTION

A rape perpetrated by the victim’s spouse is referred to as marital rape. Rape is still defined as unwelcome sexual contact or penetration of another person. As a result, establishing that no consent was gained is critical in proving rape. Often, the victim bears the burden of proving a lack of consent.

It is believed that consent does not exist in some situations, such as when dealing with children, because they are legally deemed to be incapable of consenting to such sexual acts. In contrast, authorization is presumed to exist in some situations. This presumption is commonly formed when the criminal and victim is married.

The concept of marital rape becomes diametrically opposed in these circumstances.

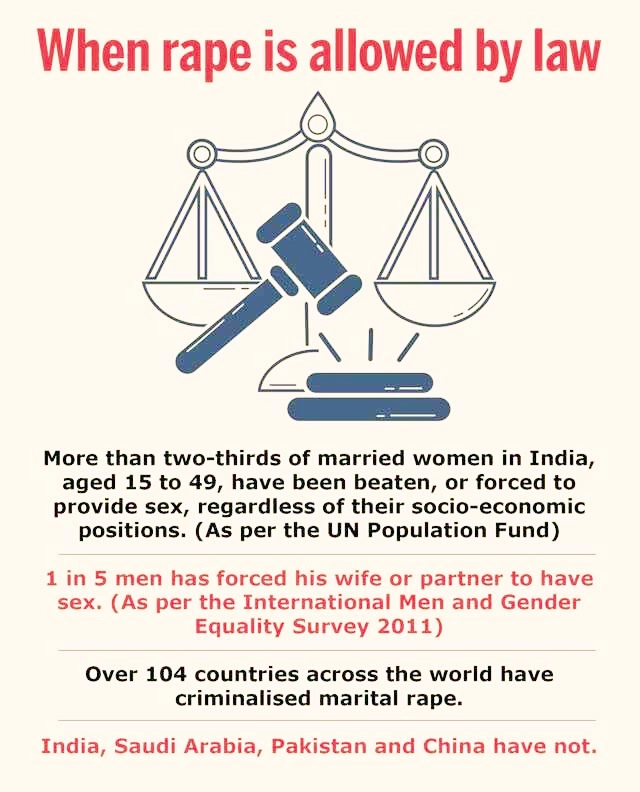

Less than half of the nations in the world now have laws that forbid raping a spouse. Several countries, including India, do not consider marital rape to be a crime. Even in countries that view rape as a crime and impose sanctions for it, the spouses of the perpetrator and victim are exempt from such rules. This phrase is also known as the exemption for marital rape. The wife’s perception that she was her husband’s slave was the initial justification.

The legislation and parliamentary discussions surrounding India’s prohibition on marital rape are examined in the second portion of this article. The four main reasons we listed are the same as those used by the Indian government to justify not making marital rape a crime.

The primary subject of section 2 is these arguments. The prosecution’s case alleging marital rape will be explained in sections three through five. We will also amend the legislation to support this after demonstrating in favor of laws that criminalize marital rape in Part 6.

Chapter 2 – MARTIAL RAPE CRIMINALISATION DEFICIENCY AS A FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS VIOLATION

One of the arguments against criminalizing marital rape—that it would constitute a disproportionate interference with the institution of marriage—was shown in the preceding section. The foundation of our society, regarded to be a sacred institution, is marriage.

It is considered to be extremely private, and the State is reluctant to intrude into such a sensitive area. The purpose of this is to protect residents’ privacy, which would be violated if the State intruded into this area. Therefore, no two people are forced to get married or get a divorce by the State.

However, it might be troublesome when the State refuses to access this private zone, even in very specific circumstances. For example, in order to make abuse against a married woman criminal, the State would have to intrude into this private domain.

If the State does not act, the lady will be without legal recourse. As a result, the State must occasionally intrude into this personal space. Although marital rape happens in the private realm of a marriage, the State has a duty to enter that area. If the State does not interfere in this private zone, a woman who has been sexually assaulted by her spouse is helpless.

Both Articles 14 and 21 of the Indian Constitution identify marital rape as a violation of women’s fundamental rights. We argue in this section that because marital rape is not a crime, a woman’s fundamental rights are being violated. Although marital rape happens in the private sector of a marriage, it is the role of the State to breach that curtain.

However, a review of court rulings involving issues usually regarded as being in the marriage and family spheres of privacy brings to light the judiciary’s reluctance to include fundamental rights in this private sector. In this imaginary private space, which it has constructed, the judiciary has refused to uphold and apply fundamental rights. This has resulted in putting to rest the argument that marital rape violates fundamental rights. This is due to the fact that fundamental rights are not considered to have any place in the marital realm.

2.1 A PRIVATE SPHERE IS MADE WITHOUT THE PROTECTION OF FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS

The history of decisions addressing the recovery of marital rights must be carefully examined in order to understand why the judiciary has been reluctant to confront fundamental rights in the private domain.

This is due to the analogy between the conjugal rights’ restitution argument and the constitutional law concerns with marital rape. The conjugal rights’ restitution was initially established under English law, even though it is no longer used there. A married couple may be ordered by a court to cohabitate or to have their conjugal rights restored against one another.

The Hindu Marriage Act of 1956 in India states as much under Section 9. The section’s main tenet is that the court may grant a conjugal rights restitution ruling if one spouse refuses to cohabitate with the other without good cause.

Women have frequently been harmed by conjugal rights’ restitution. Frequently, males compel their wives to wed. The primary question in this argument, similar to the marital rape debate, is whether the State has the authority to compel a woman to have sex with her husband. This lawsuit and related constitutionality challenges have been sent to the Supreme Court and the High Court for review.

The very first instance to contest the constitutionality of the conjugal rights’ restitution as laid down in the Hindu Marriage Act was the matter T. Sareetha versus T. Venkata Subbaiah decided by the Andhra Pradesh High Court. The Court was presented with the claim that Articles 14, 19, and 21 of the Constitution.

The court recognized the harm that this measure would affect women and stressed the significance of sexuality. In the same part, the Court expresses its agreement that “no positive act of sex may be imposed upon reluctant persons, for there is nothing more revolting to human dignity and awful to the human spirit than to subject a person by the long arm of the law to a positive sex Act.”

Nonetheless, the Court found that the “marriage domain” notion and the principle of conjugal rights restoration are incompatible. It’s worth noting that the idea of forced sex can exist even within the context of marriage, even if the Court seldom acknowledges it. Nonetheless, the Court determined marital rights.

A petition questioning the validity of the conjugal rights’ restitution was presented to the Delhi High Court in Harvender Kaur v. Harmander Singh Choudhry. The Court maintained Section 9 of the Hindu Marriage Act’s constitutionality after Sangeetha. According to the Court’s ruling in this instance, conjugal rights’ restitution was created to “defend the institution of marriage,” not to force someone to remain with their spouse. It also rejects the idea that women would be compelled to restart their conjugal relationships with their husbands as a result of a conjugal rights’ restitution decision.

The application of constitutional law to a husband and wife’s regular domestic relationship will strike at the very foundation of that relationship and provide a fertile ground for contention and argument. It will allow for limitless legal action in relationships, which should certainly be kept as far away from such possibilities as feasible.

The domestic community does not rely on legal documents that are wax- and seal-sealed. on constitutional law, either. It is based on the moral glue that binds people together and creates a “two-in-one-ship.

By doing this, the Court dissociates the constitutional consideration of the recovery of marital rights from the matter of sex and personal freedom and rejects even addressing it. This lowers the debate over the restitution of marital rights to a legislative matter without relevance to the Constitution. Because the Government has established a private domain, the Constitution and the fundamental freedoms it protects have no relevance in this situation.

2.2 SUGGESTIONS FOR THE CONSTRUCTION OF A PRIVATE DOMAIN

These cases show two opposing viewpoints that are crucial in separating marital rape from a violation of basic human rights. Second, an impenetrable “marriage domain” emerges, beyond the reach of constitutional legislation. As a result, while rape is usually regarded as a violation of a woman’s fundamental human right, this logic no longer applies in the “marriage arena.”

This is because marriage is not protected by fundamental rights. In legal theory, the distinction between public and private places has been questioned. Some family matters were formerly thought to be too private for the law to control.

As a result, many people thought that the Act only applied to public issues. As a result, it was widely assumed that the Act only related to public concerns and that corporations were immune from its provisions. Nevertheless, Frances Olsen argues in The Feminist Critique that the idea of specific private zones creates a situation in which individuals who are harmed lack legal remedy, making legal action against those who harm impossible.

The claim that family law is immune from constitutional law is false. The Indian Constitution was created to protect equality and to abolish practices such as casteism even in secluded areas, demonstrating the goal to abolish these distinctions between public and private spheres. Laws dealing with this difference have gradually but inexorably vanished as a result of laws addressing violence against women in married partnerships.

Women who have been victims of marital abuse already have a range of civil and criminal remedies available to them under the Protection Of Women From Domestic Violence Act, 2005, and IPC section 498A. This was done to protect the rights of these women.

As a result, the notion that there is a zone devoid of constitutional rights is no longer true in the contemporary situation. It is simply utilized to conceal particular sorts of battle brutality that the legislative and judicial branches are uncomfortable recognizing and confronting. As a result, we believe that the exemption clause in Section 375 of the IPC can be used. This subject has forced this differentiation to fade gradually but eventually.

The notion that there is a region devoid of constitutional rights is thus no longer true in the modern world. Just certain forms of combat violence that the legislative and judicial institutions are uncomfortable recognizing and confronting are covered up with it. As the exemption language in Section 375 of the IPC can be interpreted in accordance with constitutional law, we contend that it does not pass the constitutionality test, as we shall demonstrate in more detail.

2.2.1 THE SELECTIVE INFILTRATION OF THE PRIVATE SPHERE BY THE STATE

The High Court of Andhra Pradesh determined in Sareetha that the concepts of coerced sex and marital privacy were incompatible. They interpret the phrase “marriage privacy” to imply that the state cannot compel a couple to reconcile since to do so would be against their rights to privacy.

The Delhi High Court’s interpretation of marital privacy in Harvender Kaur states that the Constitution cannot be applied in such cases. The term “marriage privacy” was used by the court in Harvender Kaur to refer to a private area into which the court has no right to invade. This is an example of the various perspectives on marriage privacy and the inherent unpredictability that its application may bring about.

The State’s contradictory actions in this regard serve as evidence of such. As previously mentioned, the court in Harvender Kaur refused to take into account the alleged infringement of a woman’s Article 21 rights owing to the “marriage domain” defense.

The State still meddles in the private sexual affairs of two consenting adults, despite efforts to get Section 377 of the IPC decriminalized. State officials regularly uphold legislation that forbids sexual activity between consenting individuals. In this instance, the State is not hesitant to trespass on this imagined private space. This may also be seen in the limits on abortion, where women are constantly harassed in this way and have their privacy invaded.

This demonstrates that the State has only slightly encroached into this space. This idea of the “private sphere” is open-ended and subject to alter at the State’s whim. Based on its beliefs, the State determines the realm’s impenetrability and privacy. The State may decide that it is acceptable to penalize behaviors like adultery or sexual activity between consenting adults of the same gender when marital rape takes place in a private setting.

2.2.2 THE SHIFT FROM PRIVACY TO INDIVIDUAL SOVEREIGNTY IS ESSENTIAL

Thus, we contend that we must give up privacy As was done in K.S. Puttaswamy versus the Union of India, the private domain can be defined in a progressive way that promotes women’s rights. Since conjugal rights’ restitution did not preserve the concept of “marriage privacy?, the court found that it was illegal even in the case of Sareetha.

Yet, the main thrust of the ruling is on how being forced to remain with one’s spouse injures a woman’s right to individual autonomy. So, in Sareetha, the Court might not have relied on the marital realm issue but rather on the concept of human independence and freedom to strike down the unlawfulness of Section 9 of the Hindu Marriage Act. the argument even if it promotes a woman’s right to sexual and personal autonomy.

However, although Harvender Kaur stated that the concept of personal autonomy just wouldn’t be applicable in this circumstance since it had previously been used, she was permitted to use the word “marriage privacy” in an entirely different meaning. This draws attention to the nuances in the interpretation of this phrase.

According to renowned feminist academic M. Nussbaum, we must concentrate our efforts on fighting for women’s rights in terms of parity for autonomy and decision rather than relying on the privacy line of argument.

In this article, we also argue that, rather than emphasizing the woman’s right to privacy, we should emphasize the woman’s individuality and personal and intimate choice. As a result, in this Part, we’ve demonstrated how the concept of a private sector free of constitutional law is faulty.

We’ve also shown how, ideally, the conversation should deviate significantly from the privacy problem and toward autonomy. After the demonstration that the provisions of the constitution apply to weddings as well, the next section will focus on Article 14 and how the exemption clause undermines them.

CHAPTER 3 – EXEMPTION CLAUSE ANALYSIS IN LIGHT OF CONSTITUTIONAL LAW

In this section, we try to demonstrate that the exclusion clause is unconstitutional after demonstrating that the concept of a private sphere is incorrect and that constitutional rights have an impact on marriage.

We must return to the struggle that developed after Sareetha and Harvender Kaur before we attempt to do the same. In Saroj Rani v. Sudarshan Kumar Chadha 6, the Supreme Court endeavored to resolve the conflict in light of these conflicting rulings and eventually maintained the conjugal rights’ restitution’s validity.

The Court approved Harvender Kaur’s verdict. On closer inspection, it differs slightly from the Delhi High Court’s ruling. In this case, the Court maintains that the conjugal rights’ restitution’s goal is to protect marriages, thus when viewed from this angle, it is not in violation of either Article 14. The Court concludes that as there is a fair classification, the goal of the law justifies having a distinct statute for married women, and thus does not infringe Article 14.

Applying this to the discussion of marital rape, the argument would be that even though the law accords married women different rights than unmarried women, doing so would not violate Article 14 because marriage serves as a legitimate classification.

The argument is that marriage satisfies the standards established for justifiable differentia under Article 14 of the Constitution, not that rape per se is not unconstitutional. Consequently, even if rape violates Article 21,” it is permissible when it is referred to be “marriage” rape because it amounts to a legitimate classification.

We will show how the definition of marriage has altered legally, making women equal partners in marriage, to refute this. We will use this to demonstrate how the evolving concept of marriage prevents the marital rape exception from meeting Article 14’s standards.

Over the past few decades, Indian law’s view of marriage has undergone tremendous change.

Currently, specialized rules for each religion control the area of marriage, or religion-neutral legislation will apply if the parties to the marriage so choose. The dynamics of the spousal relationship have changed as a result of the codification of marriage regulations.

The traditional perspective of women’s place in marriage was to be seen as the husband’s property from the very beginning. Keeping in mind gender norms, it was to see the woman as less than the husband, if not as property.

The status of either the husband or the wife in the marriage is the same as before the codification, nevertheless. There is no distinction made between the position of the wife and the husband in codified laws like the Hindu, Christian, Parsi, and Special Marriage Acts.

It is not possible to imply that women are the husband’s property given the strong constitutional protections for gender equality. The status of husband and wife in Islamic law is equal, dispelling the idea that women are property, even when couples marry under Islamic personal law, according to both religious scholars and case law. Furthermore, great progress has been made in a woman’s entitlement to property in the marriage as well as her right to divorce, reinforcing her status as an equal partner.

The idea that wives should be treated as property by their husbands is therefore unjustified. Given the extensive case law and constitutional jurisprudence in favor of gender equality, as well as the Supreme Court’s recent decision to move beyond the binary of man and woman to recognize the third gender, an argument that women are treated less favorably than men in marriage will never satisfy the requirements of Article 14.

By featuring the correspondence of the couple, we likewise discredit the contention that marriage involves the spouses agreeing to sex. The issue with banters about agreeing to sexual activity in a marriage is that it is as often as possible saw in two unmistakable classes.

First off, marriage is inseparably connected to sexual connections. The subsequent point is that marriage doesn’t suggest a sexual relationship. Legitimately, the affirmation that marriage is totally separated from sexual connections doesn’t hold a lot of weight, as confirmed by the fact that so many separation claims depend on sexual connections.

Be that as it may, marriage can’t suggest agreeing to every single sexual activity. Regardless of whether we envision sexual connections as a term in the marriage contract, agreeing to sex at all focuses during the marriage can’t be substantial under broad contract regulation guidelines. A contract that is questionable, in opposition to public strategy, or unsure isn’t substantial. As per this rationale, a marriage contract in which the lady agrees to sex consistently without respect for her substantial requirements will bomb the contract test.

Another contention is that the state would need to safeguard the establishment of marriage for cultural steadiness. One clear paradox in this approach is that the damages caused to women will far offset the damages purportedly caused to society because of a messed up marriage.

Moreover, with the State enacting brutality regulations and the Protection of Women From Domestic Violence Act, of 2005, it is certain that the State perceives that the protection of the establishment of marriage can’t be an overall objective. Moreover, such a methodology just builds up the public-private separation and ought to stay away from it.

We have really attempted to demonstrate via these levels of assistance that there is a strong reason to treat married and unmarried women differently in terms of abuse. The requirements for Article 14 as outlined in current legislation include not just a link between the desired consequence of the law and the intended cause, but also that the law be consistent.

In Independent Thought v. Union of India, the Court recently partially rejected a provision of the exclusion scheme in Section 375 of the Indian Criminal Code. Physical intercourse with a kid under the age of eighteen is prohibited under the 2012 Protection of Children from Sexual Offenses Act. Yet, the exclusion clause allows for this if a young lady is married and between the ages of fifteen and eighteen.

The Court decided that it was unlawful to treat the young girl differently because of her upcoming marriage. This was because marriage was a categorization that made no sense. Although the Court was quick to emphasize that the decision was not so much for adulterous conjugal assault, it is good that the Court has accepted that women’s rights cannot be superseded by marriage.

Using this test, we have shown that there is no assumption of permission for sexual behavior within a marriage. Hence, in order to defend the system, it would be absurd to not condemn conjugal abuse. Furthermore, it would be inconsistent not to denounce conjugal violence in order to defend the institution of marriage when a secured right is in jeopardy and many sorts of misuse have already been declared wrongdoings. As a result, the unique case structure is illegal since it violates the Article 14 criteria.

CHAPTER 4 – THE LEGAL REMEDIES AVAILABLE TO MARTIAL RAPE VICTIMS TO PROVIDE RELIEF

A typical rejoinder to arguments in favor of criminalization is that there are already enough legal remedies, as was discussed in Part II. In the analysis that follows, we will look at civil and criminal law separately in order to show how this presumption is incorrect.

We place a strong emphasis on the necessity to criminalize rape rather than criminalizing violence against women in marriage as we analyze the lack of criminal law remedies. We also talk about how these alternatives fall short in dealing with crimes like rape at the same time. On the other hand, our case for civil law is based mostly on the ambiguity of the law and the guiding ideas of family law, which are in opposition to our support for criminalizing marital rape.

4.1 CRIMINAL LAW

The most significant arrangement, 498A of the IPC, is much of the time referred to as a practical option in contrast to genuine criminalization. 498A was added to the IPC to address instances of remorselessness to ladies explicitly. In any case, we accept that this is deficient for two reasons.

The primary explanation is that there is a reasonable qualification between brutality and assault. Assault is recognized as mercilessness by its tendency and act. The subsequent explanation is that this segment is lacking in managing assault cases.

The significance of perceiving assault as a different wrongdoing has for some time been perceived in women’s activist writing. Besides that, the wrongdoing of assault is unmistakable because of the idea of the actual wrongdoing.

It is unquestionably savage; in any case, this remorselessness is unmistakable from physical and mental brutality. It is related to complex man-centric power structures. This is likewise reflected in the criminal resolutions, which treat assault as a different offense from horrifying in essence mischief or attack. An adjustment of assault regulation is a decent sign for the progression of ladies in the public eye. ?

Moreover, the assault includes various prerequisites in proof law. “The nature of the wrongdoing changes how much proof and the idea of proof that can be given. The objective of condemning conjugal assault is to have the culprit ‘put in prison,’ yet additionally arraigned in court for the wrongdoing carried out.

It is superfluous to diminish the discussion over ladies’ privileges to elective systems for looking for equity when the genuine component is intrinsically commanded. As far as pragmatic application, the facts confirm that a casualty of conjugal assault might have elective components, however, this doesn’t matter to the need to condemn the conjugal assault.

We perceive that a few women’s activists contend that distinctive assault from mercilessness upholds the man-centric comprehension of a lady’s modesty. We can’t help contradicting this way of thinking for three reasons.

To start, we should recognize condemning assault and regard an assault casualty as unclean. The previous doesn’t cause the last option, yet rather different factors, for example, cultural discernments and orientation disparity do. Second, condemning assault as a particular offense underscores that the attacker or culprit has overstepped the law, not the victim.

The casualty made no commitment to the wrongdoing, and the culprit, regardless of whether her significant other, bear sole liability. This is reliable with our third explanation, which is that assault as wrongdoing varies from mercilessness because of contrasts in the idea of the wrongdoing and evidentiary necessities, as examined beneath. On account of a lady who has been truly assaulted and battered, the qualification among assault and mercilessness may not be huge; nonetheless, it is critical for the accompanying reasons.

Regardless, there is nobody size-fits-all meaning of savagery. Brutality is characterized in the 498 clarification. Be that as it may, what comprises brutality involves reality and shifts from one case to another. Certain variables, like the couple’s marital relationship, their social and disposition status throughout everyday life, their condition of well-being, and their association with their day-to-day routines, would be significant in deciding mercilessness.

Moreover, the force of responsiveness and the level of fortitude or perseverance expected to endure such mental mercilessness change from one individual to another. To put it another way, each case should be settled on its own realities to decide if mental savagery happened.

The Court has of late given bearings to forestall the abuse of 498A in Rajesh Sharma v. Territory of U.P. This way of talking from the High Court mirrors the mindset that torments the different organs of the State, and it will likewise make an indictment of instances of conjugal assault more troublesome.

Third, the most extreme penalty under 498A is just three years in jail regardless of a fine. Assault conveys a most extreme sentence of life in jail. This tremendous distinction in discipline exhibits and by that the idea of savagery can’t be applied to an offense of conjugal assault.

Shockingly, Area 377 of the IPC has been utilized to condemn brutal sex. While we should commend the legal executive’s endeavor to rebuff the culprit as opposed to declining to consider the matter since it isn’t condemned under the demonstration, utilizing 377 is definitely not a suitable elective given the battle to nullify the segment considering the infringement of sexual minorities’ freedoms.

The issues brought about by the public-private separation, as well as an absence of commitment to major freedoms, are shared by the strange development. The utilization of 377 will just support these convictions. Subsequently, involving 377 will be adverse to our support also.

4.2 CIVIL LAW

Civil regulation cures possess an uncomfortable situation in conversations about orientation-based violence. Simultaneously, it isn’t outlandish to excuse the significance of civil cures since they permit women to ‘accomplish some different option from’ depending on the law enforcement framework to act fittingly and rapidly, for example, it gives women the organization to pick the plan of action, which ought to assist women with moving external the confidential circle.

Anyway when we place this conversation with regard to conjugal violence, it becomes more clear. Subsequently, while we keep on contending for criminalization, we question its adequacy on the off chance that family regulation doesn’t mirror this. In the accompanying examination, we zeroed in on how family regulation, as it right now stands, isn’t sufficiently ready to manage the idea of conjugal assault.

We never guarantee that it is inconceivable for the two of them to coincide, yet it is dangerous and questionable. How do the courts conclude how much sex is fundamental’ and when the spouse loses his ‘right’ to sex?!

There is no reasonable rule, and the limit did not depend on the legal executive imagining some essential measure of sex expected for marriage. This clearly gives the adjudicators tact in this. Moreover, the contention of philosophies that support refusal to take part in sex as a type of mental savagery and the option to reject as shown by perceiving constrained sex in a marriage is noticeable from a jurisprudential point of view.

Since the acknowledgment of the right to sex’ is a case regulation turn of events, a suitable arrangement would be for the future direction of cases to be delicate to this contention and convey decisions that are favorable to the decision of the lady.

First of all, the PROTECTION OF WOMEN FROM DOMESTIC VIOLENCE ACT of 2005 remembers sexual violence for its meaning of domestic violence. In the event that this definition could be utilized as a rule for fathoming savagery, it could likewise be utilized related.

Second, in light of the fact that the term savagery’ in family regulation is unbiased, rather than how the law on sexual violence just acknowledges women as casualties, it won’t be fitting to incorporate sexual violence inside brutality.

A more point-by-point examination is past the extent of this paper, which is worried about the criminalization of conjugal rape. When a conjugal assault is condemned, a spouse can petition for legal separation in light of the fact that.

Remarkably, the PROTECTION OF WOMEN FROM THE DOMESTIC VIOLENCE ACT, of 2005 perceives rape and is an imperative device in guaranteeing that the spouse gets protection orders, upkeep, and different advantages.

Accordingly, we have talked about the subtleties of current regulations, both crook and civil, in managing instances of conjugal assault. We desire to accomplish this by underscoring the significance of condemning conjugal assault instead of thinking about elective cures. In spite of this, we underlined the shortage of practical other options. As far as family regulation, we analyzed the job of sex and condemned it considering our support for condemning the conjugal assault.

CHAPTER 5 – THE IMPACT OF CULTURE IN CHOOSING WHETHER TO CRIMINALIZE MARITAL RAPE

The relationship between culture and law has been scrutinized throughout history. Law and culture are inseparably linked, with each influencing and being influenced by the other. On a legal level, this relationship has been extensively researched. However, we argue that this debate is irrelevant to the scope of this paper.

To start with, we have laid out that the criminalization of conjugal assault is a matter including key freedoms ensured by the Constitution. Second, having a regulation that goes against long-held social convictions isn’t uncommon in our official history. This is on the grounds that most orientation explicit regulations or regulations for underestimated networks are in conflict with our assumptions of society and its design.

Concerning interest in the criminalization of conjugal assault, which depends on the Constitution as opposed to culture, we attract a similarity with the discussion in India over free discourse and vulgarity regulations.

Article 19(2) records ‘profound quality’ as one of the justifications for confining free articulation. The High Court has deciphered ‘profound quality’ to mean public profound quality. This would suggest that in situations where the overall population believed specific discourse to be shameless, the Court would likewise believe it to be unethical.

This public impression of what is moral might be in conflict with what the Constitution imagines as moral. Established ethical quality alludes to the ethical quality of the Constitution. The ethical quality of the Constitution advances ideas like orientation balance and the right to real independence. These could exist contrary to public ethical quality. The contention that public profound quality will be important for declaring sacred ethical quality is a perilous one to take.

For instance, public profound quality may generally concur with the rank framework, as insights show. In such a case, concluding that a regulation denying lower ranks from profiting from any regulation is as per public profound quality and in this manner established is hazardous. Public profound quality is passed judgment on in light of the public’s ethics, which are a piece of their way of life and social convictions.

For our situation of conjugal assault, this term is an ironic expression when decided considering the cultural setting. This, nonetheless, doesn’t call the conjugal assault special case illegal. This is particularly evident in nations like India, where the cultural design is boundlessly unique in relation to the sacred moralities imagined.

For instance, the Share Disallowance Act of 1961 was enacted in light of the pervasive social practice of endowment in India. By and large, Sati was a typical social practice that was condemned. The fact that wrongdoing is socially OK doesn’t legitimize not condemning it.

Regardless, it ought to act as an impetus for criminalization since it demonstrates a culture that is open-minded toward wrongdoing. This contention is particularly appropriate while talking about the assault on account of the ‘assault culture that exists in the public arena, particularly in instances of spousal assault.’ I$ Consequently, we battle that the fact that our “way of life may not allow assault” doesn’t refute the illegality of not doing as such. Regardless, this ought to empower both the legal executive and the assembly to rapidly act.

CHAPTER 6 – MARITAL RAPE AND THE CRIMINALISATION VOYAGE

The necessity of criminalizing marital rape has been emphasized, and its significance has been proved. In this section, we offer a criminalization model. We evaluate it in light of the IPC’s Section 375 rape section, which is now in effect. Our major objective in this part is to present a draught law that accounts for the difficulties involved in the agreement, the proof obligation, and testimony.

The J.S Verma, group report recommended a four-pronged approach to effectively punish marital rape. It asked that the sentence be left alone, the exemption wording be removed, it is made clear that it is not a defense, and that there be no assumption of concurrence.

On the other side, the 42nd Law Commission Report favored classifying and punishing marital rape as a distinct crime rather than as “marital rape.” We’ll examine the model we believe works best in this section. Yet since it can be difficult to prove marital rape, which is a major barrier to conviction, we will also include our analysis of evidence law.

6.1 THE MARRIAGE CURTAIN AND THE PROTECTION BY LAW

To start, we concur with the J.S. Verma Report that basically eliminating the exemption proviso in Section 375 is lacking to guarantee that the uncommon conditions in instances of marital assault are covered.

This is because of the fact that it will bring about an abundance of legal caution. In Ghana, for instance, marital assault is lawfully condemned, for example, there is no exemption proviso, but since it was not expressly stated that the marriage isn’t a guard, it permitted the legal executive to approach its own structure for managing such cases.

It is feasible for the legal executive to treat instances of marital assault in an unexpected way, for example, by requiring more proof or assuming assent. This will have unexpected results. Second, it is important that the special case be plainly stated in the regulation. This is particularly obvious when there is critical social resistance to the regulation, as the peruse might be ignorant that the act is unlawful.

6.2 CONSENT AND ITS PRESUMPTION: A FALLACY OF MARITAL RAPE LAW

Second, we concur with the J.S. Verma Report that the presence of a marriage doesn’t surmise assent. In practice, in any case, the legal executive will perpetually see a degree of power to respond to inquiries of assent. There are three ways to deal with managing assent while condemning the marital assault.

The main methodology is to accept assent and put the obligation to prove anything to the person in question. The subsequent choice is to assume nonappearance of assent, and the charged should demonstrate assent. The third step is to plan a framework explicitly for instances of marital assault, which would require a survey of existing proof regulation standards.

The best of these is to treat assent similarly as we would in different circumstances. It is very hard to assume the presence of assent in a marriage in light of the fact that countering it would be almost unimaginable given the idea of spousal assault and misuse that happens inside the limits of the confidential circle.

The other limit of assuming assent is that assuming the spouse affirms in court that she was assaulted, there will be an assumption of absence of assent, which will be utilized against the charged. Both of these will be ineffectual in deciding the presence of assent’ in instances of marital assault.

Force isn’t expected under current regulations to demonstrate an absence of assent. The conditional proof is utilized to decide assent. Creating proof is very troublesome given the idea of marital assault.

This is considerably more so because of the cultural symbolism of women’s petitioning for charges of assault as utilizing it to irritate or damage or look for retribution. Considering this, we contend that there are a couple of factors that the court should consider while examining instances of marital assault.

The primary issue we would confront is that proof of the presence of sex won’t sum up much in instances of marital assault. This is because of the implied basic suspicion that wedded couples will take part in sex with one another. Accordingly, laying out the absence of assent is more troublesome than in more bizarre assault cases. 33 states in the US of America have a few impediments on how much power is expected to demonstrate marital assault.

Thus, the overall principle that power isn’t a capability may not make a difference in these cases. Be that as it may, the circumstance isn’t irredeemable on the grounds that, measurably, most instances of marital assault happen close by indications of actual injury or different types of brutality, including mental remorselessness. Subsequently, the overall guideline of the absence of power not being a factor will be tested in instances of marital assault.

6.3 APPROACH TO PENALIZING

Third, we concur that there ought to be no variety in condemning strategy. The condemning approach is illustrated in Section 376 of the IPC. Assault conveys a sentence of seven years to life in jail.

Notwithstanding, 376B, which manages a couple living separated, has an alternate condemning strategy with the discipline going from two to seven years. Notwithstanding, we contend that this is unlawful based on uniformity, as stated in Article 14.

There is no legitimization for an indulgent discipline strategy in light of the presence of marriage. Considering this, we suggest that 376B be canceled and the condemning strategy fill in as it does.

6.4 INDIA PENAL CODE, 1860, AND THE AMENDMENT REQUISITE

In past sections, we contended the criminalization of marital assault. Considering every one of the contentions progressed, we propose the accompanying criminal regulation corrections.

In the first place, eliminate the Section 375 exemption condition and supplant it with another clarification provision expressing that marriage isn’t a protection.

CHAPTER 7 – CONCLUSION

The conversation about marital rape is critical to establishing true equality for married women, who are generally consigned to the seclusion of their homes in a political and legal debate. It is critical to recognize that there is a significant legal gap that is currently weakening women’s constitutional rights to equality and autonomy. As we have repeatedly demonstrated, there are compelling political, legal, and cultural arguments against criminalization.

These arguments, which are packed with ideas about the family, marriage, and women’s roles in society, were carefully examined to establish their plausibility. We asserted that Section 375 of the IPC’s exemption clause is unconstitutional in its existing iteration.

As a result, it fails the equality test provided in Article 14. Furthermore, we have established that there are no feasible legal alternatives, thus our focus should be on criminalizing it rather than researching alternative approaches.

Additionally, we contended that the fact that marital rape is not allowed in our culture doesn’t really rule out its legalization.

In light of all of this, we propose an approach to criminalizing marital rape. We initially proposed that the exemption clause be removed. Furthermore, we propose that it be made plain that the accused’s and the woman’s marital status will not be considered a defense.

Also, we suggest maintaining the consistency of the sentencing guidelines. Lastly, we suggest alterations to the Evidence Act to make sure that it takes the difficulties of prosecuting instances of marital rape into consideration.