UTTAR PRADESH GOVT NAMES AND SHAMES THE UNFAVOURABLE

INTRODUCTION:

In 2020, India witnessed one of its most powerful reassurances of citizen unity in the form of the anti-CAA protests.

In an otherwise gloomy, and troublesome time for a country witnessing the wrath of communal hatred, India’s youth took it upon itself to set the record straight on its unflinching belief in the constitutional tenets of secularism and equality.

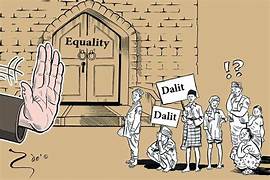

The infamous Citizenship (Amendment) Act, of 2019, aimed at the implicit relegation of India’s 172.2 mn Muslims[1] to second-class status, going against the dreams and aspirations of the framers of our constitution, by an unwarranted exclusion of persecuted Muslims from availing fast-tracked citizenship in India. The passing of the said Act was followed by a national and international uproar. Protests engulfed India.

These protests were the reawakening of India’s timid conscience. With Gandhi’s methods, and the Reverend King’s zest, the spirit of India marched on the roads for equality, as the people watched the world’s largest democracy reclaim its most cherished attribute- unity in diversity.

Scenes of the Sikhs organizing Langar for the protestors, Hindus, and Muslims walking hand in hand to face police brutality and students swearing by the Constitution to win the fight against hatred, became the order of the day. People across the country rejected the Act and left no stone unturned to wield legal and political means to register their disapproval.

While protestors were jailed and framed to quell dissent in several parts of the country, students of esteemed institutions were attacked by the Delhi police within the campus. Unsurprisingly, adding to it, the incumbent government of Uttar Pradesh engineered a dangerous administrative cum political plan to display pictures and residential details of several protestors accused of vandalism to name and shame them publicly.

Thankfully, the judiciary came to the rescue against the spectre of demagoguery. The Allahabad High Court took suo moto cognizance of this public humiliation of ordinary citizens to jeopardize their reputation, terming it an injury to the Right of Privacy, guaranteed in the constitution of India.

STATE’S RESPONSE:

In the court, the state acknowledged the absence of any statute permitting executive authorities to put up posters with images and details of citizens. However, the disclosed objective of the action in the state’s submission was “to deter the mischief mongers from causing damage to public and private property.” [2]

THE COURT’S CONCERNS REGARDING THE PRIVACY OF INDIVIDUALS:

- The prime consideration before the Court was to prevent the assault on fundamental rights, especially the rights protected under Article 21 of the Constitution of India. This right of personal liberty keeps individuals free from restrictions or encroachments on their person, whether directly imposed or indirectly brought about by calculated measures.

- This fundamental right provides lungs to the edifice of our entire constitutional system. The slightest injury to it is impermissible as that may be fatal for our values designed and depicted in the preamble of the constitution.[3]

- The court raised questions over the legitimacy of the said act of the district and police administration of Lucknow, which is alleged to be in conflict with the right to life and liberty. The poster in question is seeking compensation from the accused persons and further confiscation of their property, if they failed to pay compensation.

- Such depiction of the personal data of individuals may amount to unwarranted interference in the privacy and security of an individual. Privacy underpins human dignity and key values of a democracy.

- The cause as such here is the undemocratic functioning of government agencies which are supposed to treat all members of the public with respect and courtesy and at all times should behave in a manner that upholds constitutional and democratic values.[4]

- Every democratic country sanctifies domestic life; it is expected to give him rest, physical happiness, peace of mind and security. Nearly every country in the world recognizes a right to privacy explicitly in their constitution. However, in India, the Courts have found the right protected as an intrinsic part of life and personal liberty under Article 21 of the Constitution of India.

- Therefore, while the government can charge people for vandalism of public property, the issue at hand is not the validity of compensation fastened, but rather the disclosure of personal details of the accused persons.[5]

- No power is available to the police or the Executive to display personal records of a person to the public at large.

- In Malak Singh and others Vs. State of Punjab and Haryana and others,[6] the Supreme Court held that even for history sheeters there is no question of posting the photographs even at police stations.

- The security of one’s privacy against arbitrary intrusion by the police is basic to a free society.[7] Further, the government must see to it, that a less intrusive measure could have been used without unacceptably compromising the achievement of the objective.[8]

- However, in Justice K.S.Puttaswamy(Retd) vs Union Of India, 2018, the Supreme Court has clarified that like most other fundamental rights the right to privacy is not an “absolute right”. A person’s privacy interests can be overridden by compounding state and individual interests subject to satisfaction to certain tests and benchmarks, which are liability, legitimate goal, proportionately and procedural guarantees.[9]

- Consequently, on scaling, the act of the State lacks the necessity of legitimate aim to publish personal data and identity of individuals in a democratic society. Since the object here is to deter people from participating in illegal activities, the action fails the test of a rational nexus between the object and the means adopted to achieve them.

- Thus, the extent of interference must be proportionate to its need. Despite the presence of lakhs of accused individuals facing allegations of committing serious crimes in the state of Uttar Pradesh, the placement of personal data of selected persons reflects a colourable exercise of powers by the Executive.[10]

- Further, the accused persons, in no manner, are fugitives.

- Thus, there the court had no doubt that the action of the State is an arbitrary, unwarranted interference in the privacy of people and by extension, is in violation of Article 21 of the Constitution of India.

- Consequently, the court ordered the immediate removal of all such banners across the state.

CONCLUSION:

The decision of the Allahabad High Court was challenged in the Supreme Court, wherein the State cited the judgment of the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom in the matter of an application by JR38 for Judicial Review (Northern Ireland), (2015) UKSC 42. This case saw a direct conflict between such ‘Name and Shame’ orders under Britain’s Operation Exposure and Article 8 of the European Convention of Human Rights (or the ECHR) guaranteeing the Right of Privacy to all individuals.

However, the major point of difference between the two cases was that of the objective behind the means adopted. In Operation Exposure, the purpose was identification to further the investigation, whereas, in India’s case, the purpose of putting up posters was to name and shame the protestors.

Being members of the minority community, also opens them up to security concerns fearing mob justice, because of being criminalized and stigmatized in society. Thankfully, the Judiciary checked the arbitrary exercise of power by the state in the aforementioned case, thus, upholding the aspired standards of constitutionalism by the framers of the Constitution.

India is increasingly witnessing arbitrary state action, particularly against the minority community. This trend of the majority’s silence, and implicit approval of bulldozing Muslim houses, putting up images and personal details of Muslim protestors, or unleashing an online army of trolls on Muslim journalists raising their voices against such malicious dehumanizing of the entire community is worrisome, to say the least. In a liberal democratic society, such state-sponsored targeting of minorities is unacceptable.

Hence, we find the judiciary, the journalists and the youth of India continue this strife to safeguard the Human Rights of all individuals against the leviathan.

REFERENCES:

[1] – Census, 2011

[2] [3] [4] [5] [10] – Public Interest Litigation (PIL) No. 532 of 2020

[6]- AIR 1981 SC 760

[7]- Frankfurter, J’s observation in Wolfs. Colorado; 338 U.S. 25 (1949)

[8]- [2013] UKSC 38 & [2013] UKSC 39 (In Bank Mellat vs Her Majesty’s Treasury, Lord Reed, in outlining the fourfold test of proportionality, followed the approach of Dickson CJ in the Canadian case of R v Oakes [1986] 1 SCR 103.)

[9]- (2017) 10 SCC 1