Indigeneity, a project of hope

Over time in the history of mankind, different nations have used a variety of terminologies to describe the groups within their geographical boundaries that they recognize as Indigenous. Definitions are usually based on a people’s descent from populations that have historically inhabited the country before the time when people from non-Indigenous cultures and religions arrived – or at the establishment of present state boundaries – who retain some or all of their own social, economic, cultural and political institutions, but who may have been deviated from their traditional realms or who may have resettled and rehabilitated outside their ancestral domains.

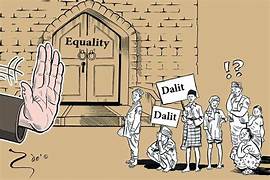

The status of the Indigenous groups in the subjugated association can be characterized in most instances as an effectively marginalized or isolated group, compared to majority groups or the nation-state. The Indigenous group’s ability to influence and participate in the external policies that may exercise jurisdiction over their traditional lands and practices is limited. This situation can continue even in the case where the Indigenous population outnumbers that of the other inhabitants of the region or state; the defining conception here is one of separation from the decision and regulatory processes that have some, at least titular, influence over aspects of their community and land rights.

The presence of external laws, claims, and cultural mores either potentially or act to variously constrain the practices and observances of Indigenous society. These constraints can be observed even when Indigenous society is largely regulated by tradition and custom. The constraints may be purposefully imposed, or arise as an unintended consequence of trans-cultural interaction. They may have a measurable effect, even were countered by other external influences and actions deemed beneficial or that promote Indigenous rights and interests.

On August 3, 1989, a Maasai activist and a former member of the Tanzanian Parliament, spoke before the U.N. Working Group on Indigenous Populations, in Geneva, Moringe ole Parkipuny, became the first African ever to spotlight the Indigenous identity. In his speech, he said, “Our cultures and way of life are viewed as outmoded, inimical to national pride, and a hindrance to progress”. As a result, pastorals like the Maasai, along with some other hunter-gatherers, “suffer from common problems which characterize the absolute plight of indigenous people throughout the world. The most fundamental rights to maintain our cultural identity and the land that constitutes the foundation of our existence as a people are not respected by the state and fellow citizens belonging to the mainstream population.”

The concept of “indigenous” had already undergone multiple transformations over a long period of time in history. The word—from the Latin indigena, meaning “native” or “sprung from the land” has been used in English since at least 1588 when a diplomat referred to Samoyed people in Siberia as “Indigenæ, or people who bred upon that very soyle (soil).” The term “indigenous” was used not only for people but for flora and fauna as well, permeating the term with an air of wilderness and detaching it from history and civilization. The racial bias intensified during the colonial period until, again like “native,” “indigenous” served as a partition, discriminating white settlers—and, in many cases, their slaves—from the non-Europeans who occupied lands before them.

Around half a billion people are under the category of Indigenous. If they were a single nation, it would be the world’s third most populous one, behind China and India. Exactly who counts as Indigenous, is still unclear. A video for the U.N. Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues begins with the title, “They were always here—the original inhabitants.” Yet many people who are now considered Indigenous do not claim to be autochthonous—the Maasai among them. According to Maasai spoken historical collections, their ancestors arrived in Tanzania several hundred years ago from a homeland they call Kerio, situated around South Sudan. Indigeneity was crafted by enterprising activists over years of strategizing, adopting ideas from Red Power, Third World nations, African and Asian anti-colonialism, and the environmental movement. With it, people sought a politics of the suppressed, aiming to protect land and sovereignty, to turn “backwards” natives into respected stewards. When indigeneity promised to deliver on these goals by attracting the assistance of international firms and organizations, the natural temptation was to exaggerate the concept until it covered as many disempowered people as possible, even at the cost of coherence.