DOES SHE HAVE RIGHT OVER HERSELF

INTRODUCTION

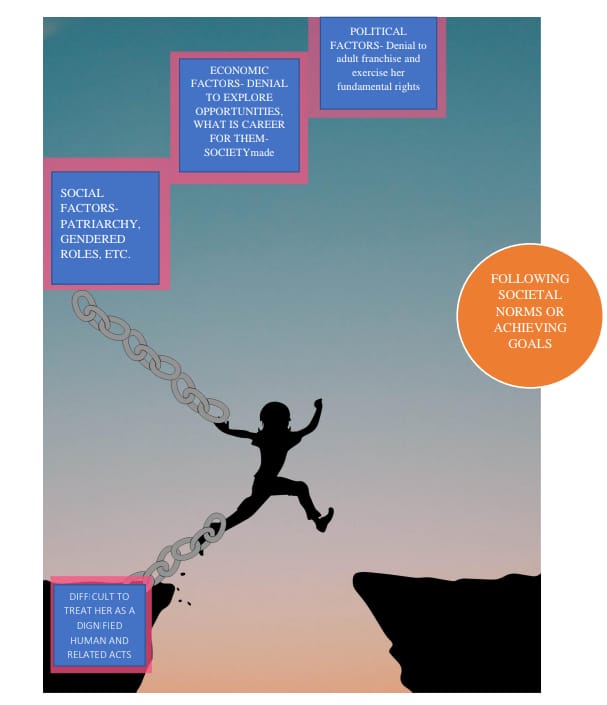

The great majority of Indian women have always been involved in endless struggles ranging from fulfilling basic necessities to political rights, from the right to life to freedom to live according to their wishes. She has gained an inch on one issue while losing a foot on the other.

Gender inequality generates and magnifies risks and vulnerabilities in areas of serious importance for humanitarian actors. Gender-based violence is one among them, but so is limited access, particularly for women and girls, to education, healthcare, agricultural lands, water sources, secure livelihood options, and suitable shelter.

Violence against women by their male partners upholds patriarchal family systems, develops a hierarchy of male dominance, and keeps women in a subordinate position. Different dimensions of women have been affected due to such practices, which have been discussed in this article.

POLITICAL ISSUES

Historically, restricting voting rights to women has restrained them, which has now taken another form i.e, male dominance to vote to an individual of his choice on a woman which ultimately signifies she is still unable to exercise her right to choose.

Even after, the 2005 amendment of the Hindu Succession Act which allowed women to be coparceners to ancestral property, women are still unable to get the property. A study from 2020 found that “only 16 per cent of women in rural landowning families own land, constituting 14 per cent of all landowners and holding 11 per cent of all land”.1

The Uttar Pradesh Zamindari Abolition Act of 1950 and the UP Revenue Code, for instance, did not include females in their definition of heirs to farmland. The Revenue Code was amended in July 2019 by the UP Cabinet to allow unmarried daughters to inherit more property from their families.

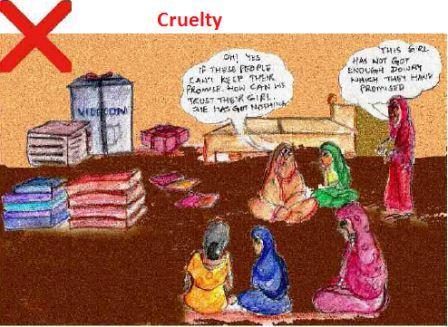

One of the main obstacles for women to demand their share of inherited property is the prevalence of male lineage. A daughter’s share is commonly held to be equal to her dowry. Women’s plight is compounded by a lack of legal literacy, women’s reluctance to claim their property rights, and flaws in the implementation of legal provisions.

Furthermore, many daughters are still stigmatized for demanding their share in parental properties as was done in the past, and many are pressured to give away their rights in favour of their brothers to maintain cordial relations with the natal family after they have wed.

Another issue is of khap panchayat, which legally has no jurisdiction to function2, but is still functional and deciding the matters of individuals. The functionality of khap panchayat has led to different socio-legal issues such as honour killings, female foeticide, forced marriages, and the prohibition of sagotra marriages. In such a scenario, females have to strictly abide by the decisions of khap panchayat or else they suicide or have to get ready for murder, which is considered as “death for good”.

Another concern is that females don’t have right over their bodies, which implies that there just live like a puppet, simply abiding by the patriarchal structure which can be substantiated by the issue of marital rape, which is not rape in eyes of the law, and her consent is implied by the fact of marriage. The consent of intercourse is taken for granted.

As per the national family health survey(2019-21), only 87.7% of rural married women participate in three household decisions. The key factors considered are decisions related to health care for herself, making major household purchases, and visits to her family or relatives. Such factors are way too less and do not even consider decisions, which also implies that females are restrained to household work and major household decisions are not taken or specifically they are not even asked.

Additionally, from the birth of a female, she is trained to live as per the gendered roles set by society. She is trained to be homely, fair, slim, and various demands from females. She is even provided education as per the region.

For example- A highly educated girl is believed to lack strong domestic skills in rural regions and low-income households, which severely limits her chances for marriage. In metropolitan regions, education is seen as a valuable advantage for women seeking a suitable partner. The enforcement of the legal marriage age and government rules requiring compulsory schooling is thus critical for enhancing their chances of attending school.

Moreover, if a woman tries to work, then there are more or less no safe workplaces, despite the laws being enforced, the reality is totally different and there are places that socially, and emotionally embarrass her and led to quitting the job.

CONCLUSION

A practical approach has to be adopted, which can work efficiently on a grass-root level. As of now, there are artificial laws, which exist on paper but in reality, they fail to protect women’s rights. At the local level, awareness camps should be launched to ensure awareness regarding the rights of women so that they can live a dignified life. Additionally, more fair and realistic laws and schemes should be initiated to solve various socio-legal issues so that women’s rights can be protected.

The use of media as well as nukkad natak should be showcased to instil the struggle that a woman faces so that a message can be communicated to society that there is a need to treat a woman as a dignified human and not as a commodity.

1 Aggarwal B, Anthwal R and Malvika M (2020) Which women own land in India? Between divergent data sets, measures and law, GDI Working Paper 2020-043, The University of Manchester, Manchester https://hummedia.manchester.ac.uk/institutes/gdi/publications/workingpapers/GDI/gdi-working-paper-202043- Agarwal-anthwal-mahesh.pdf

2 Smt. Laxmi Kachhwaha vs. State of Rajasthan (1999)1