Dust clouds from Earth's moon could help reduce global warming.

A group of US scientists this week proposed an unorthodox scheme to combat global warming: creating large clouds of Moondust in space to reflect sunlight and cool the Earth.

In their plan, they would mine dust on the Moon and shoot it out towards the sun. The dust would stay between the Sun and Earth for around a week, making sunlight around 2 per cent dimmer at Earth’s surface, after which it would disperse and we would shoot out more dust.

Reflecting sunlight is at best a way to rapidly stave off short-term catastrophic warming impacts, buying time for renewable energy transitions and removal of greenhouse gases from the atmosphere. However, there are several major engineering and logistical hurdles to overcome.

Challenges with shooting moon dust into space

At a minimum, what would be needed are Moon bases, lunar mining infrastructure, large-scale storage, and a way to launch the dust into space.

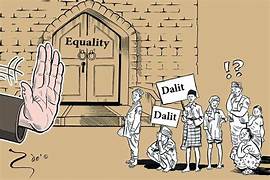

To make matters worse, there is a lack of a coherent policy or governance for space and the Moon at the global level. Many fundamental questions about human activity in space, such as the challenge of management of the growing space junk orbiting the Earth, are unanswered.

At present, at the international level, there is a patchwork of contradictory policies. The 1967 Outer Space Treaty prohibits “appropriation” of space resources (implying a ban on mining), and Article 11.3 of the 1979 Moon Treaty states that the Moon’s resources cannot become the property of a single person, group or country.

However, the US, Russia and China have not signed the Moon Treaty. In fact, the US has a non-binding international agreement – the Artemis Accords – that emphasises commercial resource extraction.

With a such contradictory policy in place, lunar mining is a fundamental legal grey area. Shooting Moondust off into space is another legal dilemma several steps down the line.

Such ineffective global legislation to regulate outer space is the outcome of major political enmities that result in the division of the world into East and West.

As can be seen that Russia and China have not signed the US-led Artemis Accord, political disagreements over Moondust deployment could prove far more dangerous. Different countries could prefer different extents of cooling, or whether Moondust cooling should be used at all.

Even the proposed “launch system” for dust, essentially a giant electromagnetic rail gun (of the kind currently used to launch fighter jets), could spark security and weaponisation concerns. These disagreements could leak into terrestrial politics, further exacerbating political divisions.

At worst, these disagreements may cascade into armed conflict or sabotage of lunar infrastructure. Space is another frontier for political conflict and one that Moon dust reflection schemes could worsen. Such conflict also compromises a cooperative and altruistic Moondust deployment.

In sum, the Moondust proposal does address some of the problems with Earth-based solar geoengineering. But it would likely be too slow to dampen the short-term impacts of climate change, and would in any case face diplomatic obstacles that may well be insurmountable.

About Solar Geo-engineering

Proposed measures to cool Earth by reducing the amount of sunlight reaching the surface are often called “solar geoengineering” or “solar radiation management (SRM)”.

Some techniques that have been proposed earlier that fall under the SRM include:

Increasing the reflectiveness of clouds or the land surface i.e. Albedo enhancement

Blocking a small proportion of sunlight before it reaches the Earth i.e. Space reflectors.

Introducing small, reflective particles into the upper atmosphere to reflect some sunlight before it reaches the surface of the Earth i.e., Stratospheric Aerosol Injection (SAI).

Focusing on eliminating or thinning cirrus clouds to allow heat to escape into space i.e. Cirrus Cloud Thinning. However, these measures that involve tinkering with natural atmosphere also have some drawbacks that cannot be left unconsidered like,

First, many experts fear that it may impair the self-regulation capacity of natural ecosystems thereby doing more harm in the long run.

Second, they may distract attention from the need for deep cuts to gross emissions which is achievable with the right political will and resource mobilization. Such measures thus pose pivotal problems of intergenerational justice.

Third, the impacts will not be limited to national borders. For instance, the unilateral use of SAI could lead to significant adverse effects in other countries, leading to conflicts. Similarly, if governments ever gain control of changing the course of potentially damaging storms, diversions that direct storms toward other countries may be seen as acts of war.

Fourth, the unintended consequences could include an adverse impact on rainfall, crop production and ocean acidification. Large-scale spraying of aerosols into the atmosphere could also deplete the ozone layer, enlarging the ozone hole. Another big risk is that when the aerosol injection is terminated abruptly this will cause rapid warming, disrupting the water cycle and leading to massive biodiversity loss. The impacts of such a “termination shock” would be much worse than the effects of climate change such measures aim to avoid.

Fifth, there is also an ethical argument that ‘do we have the right to manage and manipulate nature?’

The IPCC’s 5th Assessment Report observed that ” SRM techniques entail numerous uncertainties, side effects, risks and shortcomings” and “raise questions about costs, risks, governance and ethical implications of development and deployment”.

Way Forward

Global warming is a reality which cannot be ignored at any cost. However, the consensus on a major global ideology, plan, investment and strategy to deal with it is still unseen as evident from the continuous unproductive UNFCCC meets.

The principle of Differential but Common Responsibilities when accepted at the COP-21 under UNFCCC i.e.Paris Agreement then both developed and developing countries should fulfil their obligations as per their own declared INDCs.